This update covers developments affecting freedom of expression, assembly and association in Kazakhstan from July to September 2017. It has been prepared for the CIVICUS Monitor by International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) and Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law (KIBHR) on the basis of KIBHR’s monitoring of the situation in the country.

During this period, UN human rights bodies announced two important, precedent-setting decisions with respect to the exercise of fundamental freedoms in Kazakhstan. At the same time, the pattern of criminal prosecution of critical voices continued, with charges of economic crimes, “incitement” of discord and defamation being used for retaliatory purposes. One outspoken social media user continued to be held in psychiatric detention, while one activist fled the country due to pressure. New, restrictive draft legislation affecting the activities of media and religious communities were under consideration, and authorities continued to interfere with the rights of residents to peacefully gather and voice concerns.

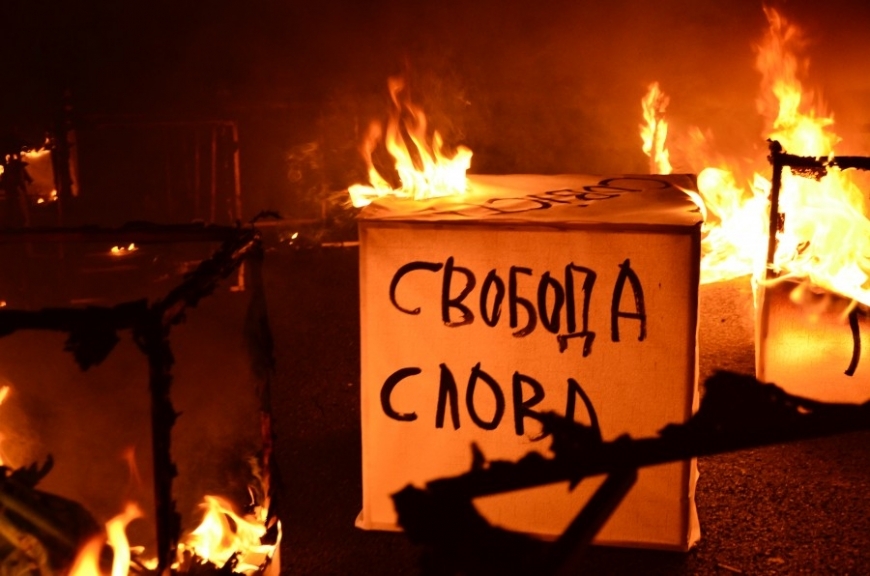

Expression

Criminal cases against critical voices

UN decision on the case of imprisoned civil society activists

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention recently published its findings in favour of a complaint filed on behalf of civil society activists Max Bokayev and Talgat Ayanov. As covered before on the Monitor, Bokayev and Ayanov were sentenced to five years in prison in November 2016 for their role in peaceful protests against land reforms. The UN Working Group concluded that the detention of the two activists is arbitrary, a result of their exercise of freedom of expression and freedom of peaceful assembly. Furthermore, the judicial process against them was characterised by violations of international fair trial guarantees. The Group called on Kazakhstan’s government to immediately release them and provide compensation.

The Group’s opinion was particularly welcome in light of the ongoing pattern of using criminal prosecution and imprisonment as a means of retaliation against civil society activists, journalists and other outspoken individuals in Kazakhstan. As illustrated by the cases described below, this pattern shows no signs of abating.

Verdict handed down against journalist

As reported before, Zhanbolat Mamay, editor of the opposition Tribuna-Sajasi kalam newspaper, went on trial in August 2017 on charges of allegedly laundering stolen money through the operations of his newspaper. On 7th September, the court handed down its verdict: it found Mamay guilty and sentenced him to three years of so-called restricted freedom, with court-imposed limitations on his freedom of movement, and a ban on engaging in journalistic activities for three years. The court also ordered him to carry out 120 hours of “forced” labour. Following the announcement of the verdict and after spending seven months in pre-trial detention, Mamay was released under the above-mentioned restrictions.

At a press conference held at KIBHR’s premises five days later, Mamay said that he considers his arrest and conviction politically motivated but that he does not plan on appealing the sentence since he sees no point in doing so. Providing a detailed analysis of the legal incongruities of the case, KIBHR Director Yevgeniy Zhovtis concluded that the court had failed to prove any criminal intent or criminal action on part of the journalist. He also pointed out that the ban on journalistic work handed down by the court, as a penalty for an alleged crime of an economic nature, shows that the charges in reality were motivated by Mamay’s professional activities. Finally, Zhovtis noted that the current Criminal Code does not allow for any penalty in the form of “forced” labour, which raises serious questions about this part of the sentence.

The Civil Society Committee for the Protection of Zhanbolat Mamay, which was established following his detention earlier this year, also denounced the case against him as politically motivated.

During Mamay’s seven months behind bars, both Kazakh civil society actors and international human rights and media watchdog groups repeatedly called for his release.

Another conviction on “incitement” charges

On 1st August 2017, an Almaty district court found Olesya Khalabuzar guilty of “inciting national discord” and sentenced her to two years’ of restricted freedom, with court-imposed limitations on her movement. The charges against Khalabuzar, who headed the Association of Young Professionals until May this year, were initiated on the basis of documents allegedly containing agitation against potential Chinese land investors in Kazakhstan. Police claimed that these documents were confiscated during searches of her apartment, as well as of the office of her organisation, carried out in March 2017 in response to a complaintfiled by a “concerned” citizen. The Association of Young Professionals has campaigned against the adoption of legislation that critics fear would allow foreigners to purchase land in the country and has drawn attention to unjust court decisions. The case against Kahalbuzar is part of a pattern: the broadly-worded criminal code provision on “inciting” national, social, religious and other discord has repeatedly been used against critical voices and complaints from “concerned” citizens have been cited as the basis for police actions also in other cases. In what is believed to be a result of pressure, Khalabuzar “admitted” her guilt during the trial. Prior to this, she announced that she is giving up her civil society engagement.

New defamation charges over Facebook post

Civil society activist Marat Dauletbayev is facing new criminal charges of defamation. These charges were leveled against him on the basis of a complaint filed by a representative of the Roskosmos company in his home town Baikonur over a post that appeared on the activist’s Facebook site in August 2017. This post presented allegations of corruption and unlawful dealings at the company. If found guilty, Dauletbayev could be sentenced to up to one year in prison. He considers that the case is aimed at silencing him and preventing him from disclosing the truth about what is going on at the Roskosmos.

Earlier this year, he was already convicted of defamation because of Facebook posts that accused Baikonur’s mayor of corruption in the allocation of land plots. At that time, the activist was sentenced to one year in prison, but he did not have to serve the sentence as he was released under an amnesty act adopted in connection with Kazakhstan’s 25-year-independence anniversary.

In July 2017, the Russian administration of Baikonur, a town hosting a well-known cosmodrome that is rented by the Russian Federation under an agreement with Kazakhstan, informed Dauletbayev that his organisation Baikonur for Civil Rights should register with the Russian Ministry of Justice in order to be able to operate lawfully. The activist stated that he does not intend to comply with this requirement since he considers it unlawful. His organisation is currently registered under national legislation in Kazakhstan.

Prolongation of forcible psychiatric detention of Facebook user

KIBHR and IPHR have already reported about the case of Natalia Ulasik who was forcibly placed in a psychiatric institution in October 2016 after a court deemed her “socially dangerous” following a hearing on a criminal case on defamation initiated against her on the basis of a complaint from her former husband. There are reasons to believe that she may have been sentenced to forcible psychiatric treatment for punitive reasons since she was known as a vocal critic of authorities on social media. KIBHR has learned that Ulasik’s treatment in psychiatric detention has been prolonged by a court decision in summer 2017, although she clearly does not pose any danger to herself or those around her. Her family only learned about the court decision after it had been handed down. Ulasik’s daughter is very worried about her mother, and she is only allowed to talk on the phone twice a month and has not been able to visit her at all given the lengthy travel required to go to the hospital for the brief rare meetings allowed. KIBHR is providing legal assistance in the case.

Advocate for journalists’ rights flees the country

Ramazan Yesergepov, chair of the board of the NGO Journalists in Danger and founding member of the Civil Society Committee for the Protection of Zhanbolat Mamay, fled from Kazakhstan to France in early August 2017, citing fears for his safety. In particular, he said that he had learned of a criminal case may be opened against him in relation to him allegedly resisting police during a forced detention on 1st August after his participation in a walk in support of political prisoners (see more under assembly). Yesergepov was previously imprisoned in 2009-2012 on spurious charges of disclosing state secrets because of a publication in the independent Alma-Ata Info weekly, of which he was the chief editor at the time. Since his release, he has been fighting for redress in his own case, as well as for the rights of other journalists. In a decision issued in 2016, the UN Human Rights Committee concluded that his right to a fair trial was violated during the 2009 trial. However, the authorities have failed to comply with this decision. In May 2017, unknown perpetrators attacked and stabbed Yesergepov in the abdomen on the Almaty-Astana overnight train when he was on his way to meet with foreign diplomats to discuss his case, as well as that of Mamay’s.

New media legislation

As KIBHR and IPHR reported in the previous update, new draft legislation approved by the government in May 2017 sets out amendments and additions to a number of laws on information and communications issues. Some of these amendments are of serious concern to journalists in Kazakhstan. The draft legislation has now been submitted to the parliament for consideration and on 14th September, the first parliamentary working group meeting was held on this issue. Ahead of this meeting, the Adil Soz International Foundation for the Protection of Freedom of Speech, KIBHR, the Charter for Human Rights and the Legal Media Center sent an open letter to the members of Kazakhstan’s parliament, proposing to exclude amendments to the 1999 Media Law from the package of draft legislation. The NGOs pointed out that the Media Law is seriously outdated, since it focuses on traditional media at this time of increasing online media, and said that the proposed amendments fail to address basic flaws of the law, while introducing amendments that would obstruct the dissemination of information of public interest and undermine freedom of expression. The four NGOs proposed establishing a working group consisting of experts from both the government and civil society to elaborate a new draft Media Law, taking into account international recommendations.

Interruptions in access to social media

On 3rd September 2017, many residents in Astana, Almaty and other cities in Kazakhstan experienced problems with using Instagram, WhatsApp, Facebook and Youtube. This happened the day after a fight between Indian and Kazakh workers at a construction site in Astana attracted widespread attention and gave rise to suspicion that the interruptions may be part of an effort by the authorities to deflect attention from these events. However, the minister of information and communications suggested that the interruptions may be due to an overload of internet traffic, as many users were looking for information on the events in Astana.

Peaceful Assembly

As covered before on the Monitor, freedom of peaceful assembly is seriously restricted in Kazakhstan. The authorities require residents to obtain advance permission for any events deemed to constitute assemblies and frequently detain and penalise participants in protests held without prior permission.

The UN Human Rights Committee recently issued an important decision on the repressive approach of the authorities to peaceful assembly. At the end of August 2017, KIBHR representative Andrey Sviridov was informed that the Committee had issued a decision in favour of a complaint he filed after being detained and fined for holding a peaceful, one-person protest in September 2009. Standing at Almaty’s pedestrian street, known as Arbat, Sviridov was holding a poster demanding a fair trial for KIBHR Director Yevgeniy Zhovtis, who had just been imprisoned over a traffic incident after facing legal proceedings marred by irregularities. Sviridov was also wearing a T-shirt with the text – “Today it’s Zhovtis, tomorrow it’s you!” – and answered questions from journalists who were present. The Committee concluded that the authorities violated Sviridov’s rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and ordered them to review his conviction, provide him with adequate compensation and revise the country’s Law on Assemblies to prevent similar violations in the future.

The UN Human Rights Committee has also previously faulted Kazakhstan’s government for infringing on the rights of peaceful protesters and called for bringing the relevant law into compliance with international standards.

This is a recent example of how widely the authorities interpret the requirement to obtain permission in advance for assemblies:

- On 29th July 2017, more than a dozen representatives of the Civil Society Committee for the Protection of Zhanbolat Mamay gathered in Almaty’s Mahatma Gandhi Park to walk together to the main post office and send appeals to foreign governments and international organisations on Mamay’s case and those of other victims of politically-motivated persecution. The participants were able to carry out their joint walk as planned. However, a few days later it turned out that police viewed the event as an assembly held without the required advance permission. Two of the participants, Askhat Bersalimov and Khalilkhan Ybrahamuly, were detained and taken to court where they were sentenced to two and three days of administrative arrest, respectively. A third participant, Ramazan Yesergepov, was forcibly detained on 1st August outside Almaty City Court where a new hearing on his appeal on the implementation of the UN Human Rights Committee decision in his case was due to take place (see background above). In connection with the detention, his blood pressure increased to a critical level. In spite of this, he was first taken to a police station for questioning on the walk in support for political prisoners before being transferred to emergency care.

In another recent example of the state’s interference in the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, an elderly woman was detained:

- On 24th August 2017, Raisa Dyusembaeva was holding a peaceful protestin central Astana, across from the presidential residence and the Supreme Court. She was wearing a two-part placard with photos of political prisoners, as well as photos from the 2011 Zhanaozen events, when over a dozen people died in clashes with police after a protracted peaceful workers’ strike. Her son was accompanying her. After she gave an interview to the Kazakh service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), which was present and filmed the incident, police disrupted the protest and eventually detained Dyusembaeva and her son and forcefully placed them on a police bus that took them to a local police station. They were released after being asked to sign explanatory statements. In connection with the detention of the civil society activist and her son, one police officer also threatened the RFE/RL journalist who filmed the incident.

Association

New draft legislation on religion

As covered before on the Monitor, Kazakhstan’s 2011 Law on Religious Activity and Religious Associations provides for serious restrictions on the activities of religious communities and basic religious activities such as worship, religious teaching, missionary work and the distribution of religious literature. New proposed amendments to this and other laws that regulate religious activities and associations introduce additional and problematic restrictions in this respect. The draft provisions, among others, increase penalties for conducting religious rites or distributing religious literature without prior state permission, prohibit religious teaching outside religious education organisations, provide for increased state control of the activities of religious communities and set out new grounds for banning the activities of such groups. The proposed amendments, which were drafted by the Ministry on Religious and Civil Society Affairs, are expected to be submitted to the parliament in the near future.

SOURCE: