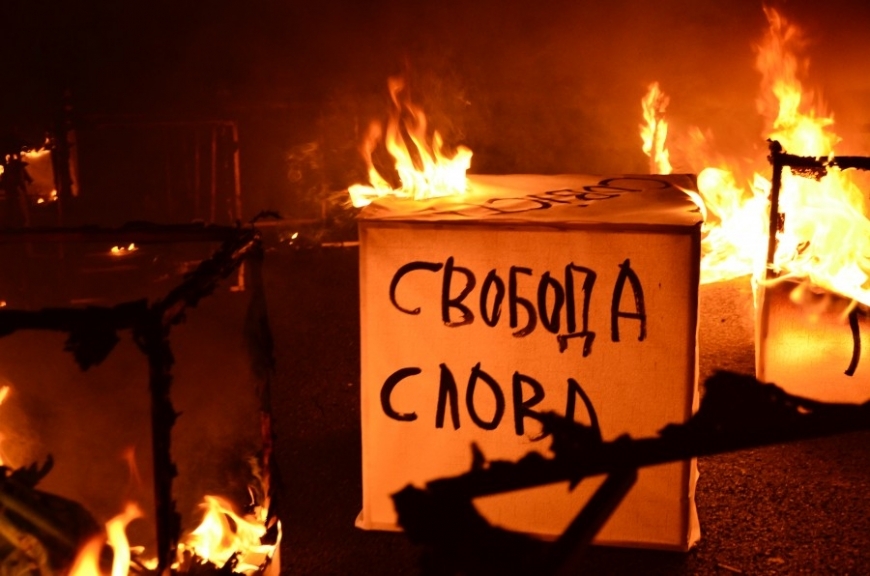

The current climate for media freedom and free speech in Kazakhstan is seriously concerning. As described below, the curtailment of freedom of expression includes restrictive legislation, pressure on independent and outspoken media, arbitrary blocking of websites, and criminal prosecution of journalists, political and civil society activists and social media users because of the exercise of their freedom of expression.

MEDIA LEGISLATION

A tightly-controlled and overly-regulated media epitomises a situation where critical speech is widely suppressed in Kazakhstan. The legislation governing media outlets requires compulsory registration and gives the authorities broad grounds upon which to impose sanctions on critical outlets.

In November, the Ministry of Information and Communications put forward draft amendments to several laws affecting the media. While media representatives welcomed some of the new provisions, such as a proposal to reduce penalties for media outlets for violations of a technical nature, other amendments have drawn criticism from civic groups. However, other provisions have been viewed as a threat freedom of expression. In particular: provisions that make it an obligation for journalists to verify the accuracy of all information received; impose new restrictions on obtaining information from public bodies; and requires internet users to undergo electronic identification before making comments on online resources.

PRESSURE ON INDEPENDENT AND OUTSPOKEN MEDIA OUTLETS

Following the closure of a number of independent and government-opposed media outlets in the last few years, only a few remain operational in the country. These media are subjected to ongoing pressure, including defamation lawsuits initiated by public officials and other public figures who demand large amounts in moral compensation because of articles about corruption allegations, alleged misconduct or other issues that do not please them. In most cases, courts rule in favour of such lawsuits, resulting in decisions that seriously threaten the financial viability or even survival of the outlets in question and contribute to self-censorship among media and journalists.

These are a few recent examples documented by KIBHR:

- In December 2016, an appeal court upheld a lower level court decision against the ‘Uralskaya Nedelya’newspaper, ordering it to pay a total of 5 million Tenge (around 10 000 EUR) to a police officer over an article that recounted an apology he offered after the newspaper’s chief editor was fined for covering peaceful land reform protests. In another defamation lawsuit facing the newspaper, regional health authorities are requesting 10 million Tenge (some 28 000 EUR) in compensation for an article about the alleged disappearance of a newborn in a local hospital;

- In November 2016, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction againstJas Alash newspaper and its co-defendants, who a year earlier had been found guilty of defamation because of an article about a legal case against a medical professor and member of the bureau of the presidential Nur Otan party. The Supreme Court decreased the amount of compensation to be paid from 40 million Tenge (around 150 000 EUR at that time) to 5 million Tenge (around 14 000 EUR), still a sizeable amount;

- The July 2016 decision in a defamation case againstTribuna Sajasi kalam newspaper was upheld unchanged on appeal in October 2016. The newspaper was ordered to pay 5 million Tenge (around 14 000 EUR) to the director of an advertising agency, who sued it over an article discussing a criminal case on corruption against him;

BLOCKING OF WEBSITES

Blocking of news, social media and other websites is regularly reported in Kazakhstan. According to existing legislation, internet providers may be requested to block access to online resources without a court ruling e.g. if websites are deemed to contain calls for “extremist” activities, “riots” or unauthorized protests. In some cases, websites are arbitrarily blocked without any official explanation.

On Independence Day on 16th December, several social media sites including Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Instagram, as well as Google services were unavailable in Kazakhstan for several hours. Internet users believed that this may be linked to the online broadcast of a press conference that day by exiled businessman and opposition leader Mukhtar Ablyazov, who was released from detention in France earlier the same month as an extradition decision against him was cancelled. The Minister of Information and Communication, however, insisted that the unavailability of the websites had nothing to do with this interview but was the result of technical problems.

CRIMINAL CASES AGAINST INDIVIDUALS

In an alarming trend, Kazakh authorities have recently initiated a growing number of criminal cases against journalists, political and civil society activists and social media users relating to their exercise of freedom of expression.

It is of particular concern that many of these cases have been brought under Criminal Code provisions that are so broadly worded that they may be implemented to restrict freedom of expression and other fundamental freedoms in violation of international human rights law. These provisions include Criminal Code article 174 on “inciting” social, national or other discord and article 274 on “spreading information that is known to be false”, both of which have been criticized by international human rights bodies. For example, after reviewing the situation in Kazakhstan in summer 2016, the UN Human Rights Committee called on the country’s authorities to revise these provisions to ensure that they comply with the principles of legal certainty and predictability and that their application does not suppress protected conduct and speech.

‘The Committee is concerned about the broad formulation of the concepts of “extremism”, “inciting social or class hatred” and “religious hatred or enmity” under the State party’s criminal legislation and the use of such legislation on extremism to unduly restrict freedoms of religion, expression, assembly and association.’

As previously covered on the CIVICUS Monitor, the Criminal Code provisions in question have been used to persecute civil society activists.

Following an unfair and biased trial, on 28 November 2016, Atyray-based civil society activists Max Bokayev and Talgat Ayan were convicted of “inciting social discord”, “disseminating information known to be false”, as well as “violating the procedure for holding assemblies” and sentenced to five years in prison each. They were also banned from engaging in public activities for three years upon release. The two civil society activists were detained and charged in relation to their role in the peaceful land reform protests that took place in Kazakhstan in spring 2016. They actively engaged on social media against these reforms and took a lead on mobilising protests against them. KIBHR’s monitoring of the trial showed that it was marred by violations of international fair trial standards, in particular the principle of equality of arms. The sentences against Bokayev and Ayan were widely condemned, with both civil society and representatives of the international community, including the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, Maina Kiai and the European Union, calling for their release:

‘The European Union calls for the release of Mr. Bokayev, and of Mr. Talgat Ayan. We also call for Kazakhstan to cease the criminalization of dissenting opinions and to ensure that human rights and fundamental freedoms are fully respected.’

Despite the protestations from the international community, on 20th January, their sentences were upheld on appeal.

In another example of an “incitement” case against a political activist in December 2016, Kokshetau-based political activist Aslan Kurmanbayev reported that a case on “inciting social discord” had been opened against him. He said that he had been summoned for questioning by police over a Facebook post he made on 5 December where he called for boycotting the 2017 Winter Universiade and the 2017 Expo exhibition scheduled to be held in Kazakhstan. Kurmanbayev, who is a member of the opposition-minded All-national Social-Democratic Party, believes that the case has been initiated in retaliation for his expression of political positions critical of the current regime, including his calls for President Nazarbayev’s resignation, the transfer to a parliamentary form of governance and the release of political prisoners. He also said that he fears that he may be arrested at any time, even if not yet formally designated a suspect.

The overly broad provisions enable the Kazakh authorities to target social media users who have not even participated in any organised civic or political engagement. On 27th December, a court in the city of Aktobe convicted businessman Sanat Dosov of inciting social discord and sentenced him to three years in prison as a result of posting a series of social media posts critical of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Among others, Dosov wrote that Putin was “ruining” Russia, criticised his social policies and condemned Russia’s involvement in the conflict in eastern Ukraine. Dosov reportedly “admitted” his guilt during the trial, expressed regret and asked the court not to imprison him since he has six children, four of whom are underage. His lawyer argued that he should be acquitted, saying there was nothing criminal in his defendant’s actions.

In an illustration of the frequent use of the legislation, the Adil Soz Foundation for the Protection of Free Speech documented a total of 12 criminal cases on “inciting” discord and 12 criminal cases on “spreading information known to be false” over the course of 2016. At least seven of these cases ended in conviction.

In another example of of judicial harassment against journalists, on 3rd October, Chair of the Union of Journalists and National Press Club Head Seytkazy Matayev and his son KazTAG News Agency Director Asset Matayev were convicted of tax evasion (the former) and fraud (both). They were sentenced to six and five years in prison, respectively, and banned from holding leading public or business positions for the rest of their lives. On 9th December, the decision was upheld on appeal with the prison sentences unchanged but the ban on holding leading positions reduced to ten years. The charges against the two journalists are believed to be retaliatory in nature and have been condemned by both national and international media watchdogs.

The fact that defamation remains criminalised, with special protection granted to public officials is troubling in view of freedom of expression. In this case, a woman facing criminal defamation charges was confined to forcible psychiatric detention under circumstances that give rise to concern that this measure may have been used to silence an inconvenient individual.

In October 2016, a court in the city of Jezkazgan ordered kindergarten teacher Natalia Ulasik to be forcibly placed in a psychiatric institution after she allegedly was deemed “socially dangerous”. This was the conclusion of a psychiatric examination that the court ordered her to undergo when hearing a criminal case on defamation that was initiated against her on the basis of a complaint filed by her former husband. During the trial, Ulasik was deprived of qualified legal assistance as her state-appointed lawyer failed to attend some of the hearings and the court did not agree to an alternative, independent psychiatric examination of her. The conclusions of the court-ordered examination were provided to the defence only after the trial. Natalia Ulasik is not known to previously have had any psychiatric health issues and there are reasons to believe that she may have been sentenced to forcible psychiatric treatment for punitive reasons. In 2010 she was convicted of defamation and sentenced to 1.5 years of court-imposed restrictions on her freedom of movement on the basis of an earlier complaint filed by her husband. Following this, she vocally protested against this verdict and continued to post critical Facebook comments on various issues, not only issues affecting her personally but also the current situation in Kazakhstan and the policies of authorities. The October 2016 court decision in Ulasik’s case was upheld on appeal and in mid-January 2017 she remained in a psychiatric institution. A lawyer engaged by KIBHR is currently providing legal assistance to her in view of further appeals procedures.

PHYSICAL ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS

Physical attacks on journalists are regularly reported in Kazakhstan. In most cases, these attacks are not properly investigated and the perpetrators are rarely bought to justice.

On 29th December, an unknown assailant attacked and attempted to rob journalist Andrey Tsukanov in Ust-Kamenogorsk. Tsukanov was covering the court case of a convicted businessman, Kuat Sultanbekova. After being convicted to three years in prison for possession of a firearm, Sultanbekova’s sentence mysteriously grew to eleven years, prompting many to question the political motive behind his conviction. In an interview after the attack, the journalist claimed that he was attacked because authorities do not want the case to draw any publicity.

In another case, Director of the Youth Information Service, Irina Mednikova was subjected to an attack in Almaty on 12th October 2016, which she believes was related to a youth conference she was organising the following day. The unknown assailant knocked her down and took her bag containing her phone, hard drive, documents and money.

The Police have opened investigations in both of these cases, but as of mid-January 2017 no results of these had been announced.

SOURCE: