The Kazakhstan court’s decision to suspend operations at the Jehovah’s Witnesses branch office in the city of Almaty came less than two months after a 61-year-old believer was sentenced to five years in prison on a charge of inciting religious hatred. Both decisions came shortly after Russia’s Supreme Court upheld a ruling in that country outlawing Jehovah’s Witnesses as an extremist organization.

“People are a little bit afraid because it seems that it was right after the Supreme Court of Russia [decision],” Bekzat Smagulov, a Jehovah’s Witnesses spokesman in Kazakhstan, told NewsweekFriday. “We don’t know the exact reason, but what do you think? How will we think because if what happened in Russia and then we have these problems? How do you explain these things?”

Jehovah’s Witnesses, which was founded in the United States and is best known for its objection to blood transfusions and military service, has operated in Kazakhstan for 25 years. It now has 18,000 followers in the Muslim-majority country and 59 local religious organizations.

Kazakhstan passed a restrictive law in 2011 that featured stringent requirements such as forcing religious organizations to register with the government. The law, which has mainly affected Muslim minority groups, has seen the number of religious groups decline to 16 from 48, according to a 2017 report from the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF).

The situation for Jehovah’s Witnesses, said Smagulov, did not noticeably deteriorate until this

year. It was in March that Russia’s justice ministry declared that Jehovah’s Witnesses violated an anti-extremism law that has been used against groups such as the Islamic State (ISIS). The verdict was upheld a month later by the country’s Supreme Court, liquidating all 395 of the group’s local religious chapters.

An appeal against the verdict, which was widely condemned internationally, will be heard on July 17.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan has been one of Russia’s closest allies, and the two neighboring countries are founding members of multiple military and trade agreements. President Nursultan Nazarbayev has led the country since its days under Soviet rule.

Although the percentage of Kazakhstan’s population made up of ethnic Russians has declined since its independence from the Soviet Union, it remains a significant 21 percent. And 25 percent of the population is estimated to be Russian Orthodox, making it the largest non-Muslim religion in the country. The Orthodox Church, which has ballooned in numbers and power under Russian President Vladimir Putin, has been an outspoken supporter of the ban of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia.

As in Russia, Jehovah’s Witnesses say the pretense for actions against the religion is fabricated. In the case of the suspension of the headquarters’ operations, the police argued that the building did not have enough security cameras. Despite already having 20 cameras on the premises, the authorities demanded three more be installed.

“We didn’t know the reason, they didn’t explain it why they did this inspection,” Smagulov said. “They tried to find something wrong. Even though we didn’t agree, we decided to put the cameras in that day. And we showed that to the court but it did not work.”

Three weeks after the inspection, the court ordered the office suspended and fined the group around $2,000. But that was far from the full extent of the recent crackdown.

Two weeks prior to the inspection, Smagulov said, around 40 armed police and members of the National Security Committee (KNB), formerly the KGB, conducted a raid of the Almaty headquarters, with many wearing masks. It created a very public, and frightening, spectacle. The raid coincided with World Expo 2017 taking place in the Kazakh capital Astana, during which the Almaty headquarters hosted several visitors.

Claiming they suspected there were foreigners present illegally, the armed security services asked for everyone’s identification.

“We didn’t expect these people with masks,” Smagulov said. “It’s only if terrorists attack they come. But when someone with a weapon comes running, it’s a little bit scary. They sieged our property.”

Already, one Jehovah’s Witness has suffered the consequences of the crackdown. Teymur Akhmedov was sentenced to five years in prison in May after what Jehovah’s Witnesses and human rights groups have called an unjust case involving entrapment.

Akhmedov and an associate, Asaf Guliyev, who was later sentenced to five years of “restrictive freedom,” were invited to the home of a group of apparent students to discuss their faith on several occasions last summer. In reality, the students were members of the KNB and were covertly recording the conversations.

Investigators claim the responses to questions given by Akhmedov advocated “the superiority of one religion over another.” An appeal against the conviction was denied last month.

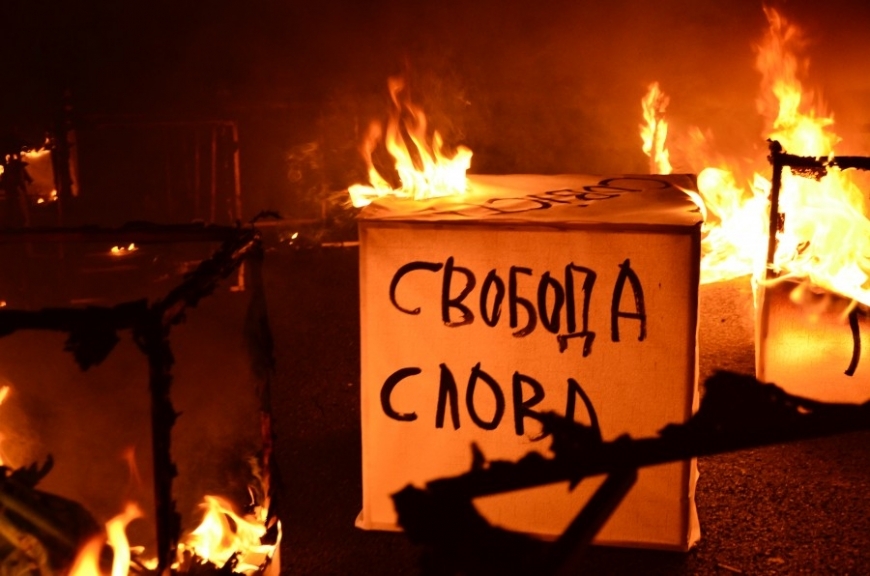

The actions go wider still. Smagulov claims that many of the country’s main media outlets have begun broadcasting and publishing negative information about Jehovah’s Witnesses. Countering the growing negative perceptions is an arduous task.

“We try to fight but we are not the majority in society, it’s hard to fight,” Smagulov said. “Usually the government tries to protect the minorities.”

An appeal against the suspension of the group’s headquarters will be heard on July 14, but, with the ever-growing hostility toward them, Smagulov added, it is becoming increasingly difficult to believe that Kazakhstan is not heading down the same path as its influential neighbor.

“We had conversations with the minister for religious affairs and he said Kazakhstan has its own way of thinking, that they’ll act independently of Russia but in reality we see different things,” he said.

SOURCE:

Newsweek

http://www.newsweek.com/jehovahs-witnesses-russia-ban-kazakhstan-634550