On January 23, a court in the city of

Almaty charged Tatiana Shevtsova-Valova with inciting animosity towards Kazaks,

the majority ethnic group in the country.

The Facebook posts also suggested that

northern Kazakstan – with its large Slavic population – might end up going the

same way as Crimea, which Russia seized from Ukraine in March 2014. They said

that if the “exaltation” of Kazaks and the promotion of their language

continued, these northern territories might come under Russian rule.

Shevtsova-Valova denies posting the

material and insists the Facebook account in her name was set up by someone

else.

This is the first time someone has been

prosecuted for using social media to spread hate speech, a crime which carries

a punishment of up to seven years in jail.

The authorities launched criminal

proceedings after being informed of the Facebook comments by a group known as

the Alliance of Bloggers of Kazakstan.

Although some members of the Alliance

are independent bloggers, overall the group is seen as pro-government. It was

set up in October at the suggestion of a number of members of Kazakstan’s

parliament, which is dominated by President Nursultan Nazarbaev’s Nur Otan

party.

Andrei Grishin of the Kazakstan

International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law sees the prosecution as a

strong message to ethnic Russians not to stir up trouble at a particularly

difficult time for the country.

“It is likely that she was seen as the

most suitable for a show trial,” he said.

Since the annexation of Crimea and the

conflict in eastern Ukraine that followed, a number of Russian nationalist

politicians have proposed “reclaiming” northern Kazakstan. Officials in Moscow have

issued disclaimers, stressing the longstanding good relationship between the

two countries. While this is true, Kazakstan’s leaders are clearly

uncomfortable about Russian actions against Ukraine and have avoided expressing

the kind of open support that Moscow would like. At the same time,

Russian-Kazak ties became even closer at the beginning of the year with the

formation of the Eurasian Economic Union.

In this fluid situation, the Kazak

government will be watching for signs of Russian separatism, whether home-grown

or imported. Extreme nationalists in Russia have been trying to reach out to

their ethnic kin in Kazakstan through various means including social networking

sites.

Grishin in no way condones the comments

attributed to Shevtsova-Valova, but points out that Kazaks as well as Russians

post inflammatory remarks on the internet.

Journalist Sergei Duvanov used his own

Facebook page to challenge the comments allegedly made by Shevtsova-Valova, and

received insulting remarks as a result.

He believes pro-Moscow comments of this

kind are designed to encourage Russians abroad to see themselves as part of a

single community.

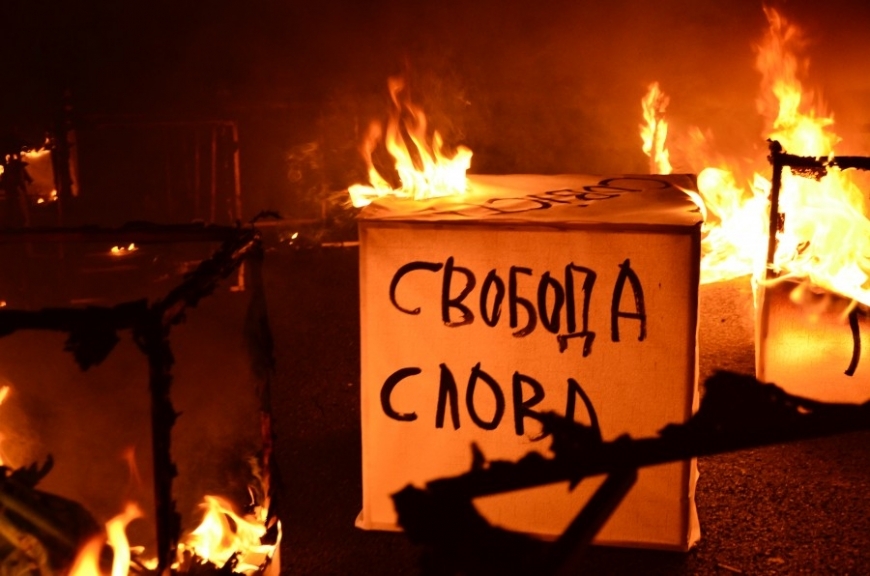

Despite his objections to

Shevtsova-Valova’s alleged hate speech, Duvanov does not believe criminal law

is the right way of dealing with such matters.

“We shouldn’t create a dangerous

precedent for criminal prosecutions for expressing one’s views on the

internet,” he said on his Facebook page.

Others disagree. Opposition activist

Jasaral Kuanyshalin told IWPR that if Shevtsova-Valova was found guilty, she

should be punished, regardless of fears of the precedent this might set.

“Such concerns are complete nonsense,

because if the regime wants to deal with [dissent], it can do so without

needing any precedent,” he said.

Political analyst Aidos Sarym is worried

about the action taken by the Alliance of Bloggers, which he sees as tantamount

to trying to impose censorship. In an interview with the news website Ratel.kz,

Sarym said it was wrong to target individuals in this way as “enemies of the

people”.

Galymbek Akulbekov, an economist and

businessman in the northern city of Karagandy, does not believe people should

be prosecuted for this kind of offence – not least because the judicial system

is seen as biased and will find it hard to address “new media” offences without

being swayed by political imperatives.

“The judiciary is not independent, and

it is likely to come up with a less than satisfactory decision that produces

more questions than answers,” he said.

More broadly, Akulbekov sees this

controversial case as a reflection of a divided society.

“I think that in the popular

imagination, the worst has already happened – Kazakstan society is already

fragmented along ethnic lines,” he said.

SOURCE:

IWPR

https://iwpr.net/global-voices/first-prosecution-internet-hate-speech-kazakstan