On

October 14, President Nursultan Nazarbaev signed off on an agreement bringing

Kazakstan into the Eurasian Economic Union.

The

union, which comes into being in January, will create closer economic ties

among the three current members – the others are Russia and Belarus. At a

summit of the Commonwealth of Independent States held in Minsk on October, a

fourth member, Armenia was admitted to the grouping. Kyrgyzstan is expected to

join next year.

Kazakstan

has always been a loyal ally of Moscow and a committed member of the Customs

Union. However, Russia’s new assertiveness and its treatment of Ukraine has

rung alarm bells. The Kazak government has no wish to be tied exclusively to an

increasingly isolated and erratic Moscow. (See Economic Union Challenges Kazak

Foreign Policy.) Pronouncements by Russian nationalists laying claim to

northern Kazakstan because of its substantial Slav population have done nothing

to calm worries about Moscow’s intentions. (Unease at Focus on Language,

Identity in Kazakstan examines some of the issues.)

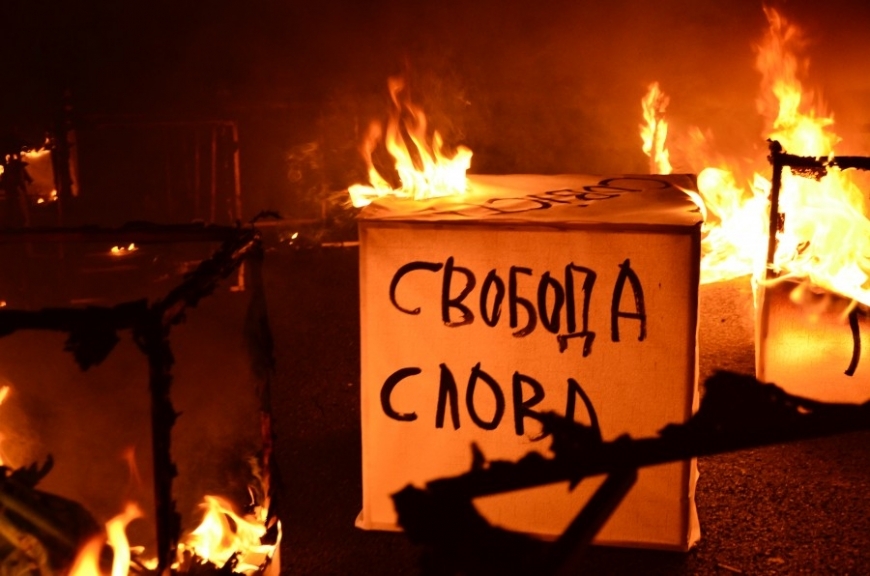

Public

concern about against closer integration with Moscow has only been expressed on

a limited in scale so far, but is real nonetheless. So far, opposition has

taken the shape of a loose alliance, operating mainly on social media and led

by Kazak nationalists opposed to what they see as the encroachment of Russian

influence.

In

March, a movement called the Anti-Eurasian Union emerged, and in May,

protestors in the capital Astana were arrested at a demonstration against

accession to the Eurasian Economic Union.

Most

recently, a group of some 30 activists held a press conference on October 6 at

which they called for a referendum on membership, warning that opening up

access for Russian businesses would threaten local producers.

Denis

Krivosheev, a financial journalist who was among the organisers of the October

6 press conference, said Kazakstan was now in direct competition with Russia,

as both countries relied on exports from their extractive industries.

“The existence of a border and independent

economic policies has hitherto allowed them them to coexist in international

markets,” he told

IWPR. “But now it’s more difficult to

mitigate the effects of competition.”

Kazakstan

was at a clear disadvantage, he added.

“Russia has been hardened by trade wars and it

has the upper hand in everything, including population size and gross domestic

product, and it could easily swallow up the Kazak market, buying off or

destroying local businesses,” he said.

Krivosheev

also warned that being hitched to the now faltering Russian economy could lead

to further weakening of Kazakstan’s currency, the tenge, which has already

suffered a sharp devaluation this February as a result of a falling rouble.

(Anger as Kazak Currency Devalued.)

The

government in Astana was trying to convince people that it could always draw on

the national fund where oil export revenues are stored.

“But it [the fund] is not a bottomless pit,” he noted.

Elite

figures have highlighted the benefits of joining the Eurasian Economic Union.

Speaking

on October 6, Talgatbek Abaidildin, a member of the upper house of parliament,

said bloc membership would produce “an increase of up to 20 per cent in GDP

growth rates” for all the states involved.

However,

many economists are sceptical.

Galymbek

Akulbekov, an economist and businessman in Karagandy, central Kazakstan, agreed

that some sectors of the economy would benefit from joining the grouping, but

this would be unlikely to offset the damage done to other industries suffer.

“The country will lose in sectors linked to

external markets – banking, manufacturing and trade,” he told IWPR.

And if

Russia is hit by more sanctions because of its behaviour towards Ukraine, this

will affect neighbours like Kazakstan, where “the government won’t be able to

compensate for losses incurred by businesses, and this will lead to stagnation

and inflation in the longer term”, according to Akulbekov.

Akulbekov

also pointed to Russia’s current efforts to replace Western imports with goods

from other markets. Together with weak levels of competition in the Eurasian

bloc area, this could reduce the quality of goods and services reaching

Kazakstan. (See also Central Asia Keen to Feed Russian Market.)

Tolganai

Umbetalieva, director of the Central Asia Foundation for Democracy, noted that

Russia is already promoting its automotive industry in the Customs Union and

excluding outside imports. As she put it, Russian cars are “not always of high

quality”.

Forbes

Magazine’s Kazakstan edition reported earlier this month that Russian lobbying

had brought about the introduction, in January 2014, of additional regulations

for cars imported into the Customs Union, including anti-lock braking systems

and a locking mechanism for child safety seats.

The

website reported that the rules were mainly meant to stop Kazak imports of cars

assembled at a General Motors plant in Uzbekistan, which is not a Customs Union

member. Removing this competitor strengthened Russian car imports to Kazakstan

in the months that followed.

Umbetalieva

said the campaign against membership of Eurasian Economic Union had broadened

far beyond its initial support-base, nationalist-leaning Kazak intellectuals,

although it was still at an early stage.

“Now liberals who oppose Russia’s policy

towards Kiev are expressing support,” Umbetalieva said

Akulbekov

agreed that the protest movement, driven by “Facebook activists” was

increasingly appealing to people with a range of agendas.

As well

the likes of Krivosheev whose concerns focused on the economic implication,

Akulbekov noted the involvement of others like political activist Botagoz

Isaeva, who fears that the Kazak language will be suppressed within a

Russian-dominated union.

“What unites them all is that they are in

favour of a referendum,” Akulbekov added.

Zamir

Karajanov, an Almaty-based political analyst, agreed that a worsening economic

climate could encourage broader support for the anti-union movement.

He

argued that its principal powerbase was likely to be among people on lower

incomes who would be most vulnerable to price rises.

Krivosheev

acknowledged that he and his fellow-campaigners needed to be realistic about

how far their movement could go.

“At the moment, it’s individual voices – some

of them more vocal, some less. It’s hardly a choir and it will probably never

become one. The wider population is busy with its own survival,” he said.

“Those at the top are content with the status

quo…. The authorities will ignore such voices of criticism] until the point

where they become more persistent and start calling for radical change.”

SOURCE:

IWPR

http://iwpr.net/report-news/eurasian-worries-kazakstan