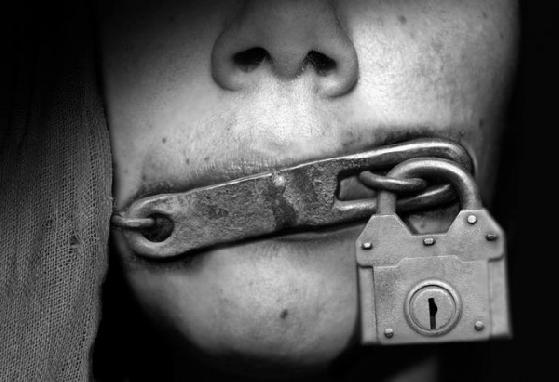

A

revised criminal code now before parliament includes a new provision banning

rumours liable to “create public disturbances”. Offenders who publish such

false information in the media, including online, would face a prison sentence

of up to five years.

Kazakstan’s

deputy prosecutor general Johann Merkel linked the new provision to the

devaluation of the national currency in February, when rumours spread on the

messaging service WhatsApp warning people to withdraw their money from the

banks.

The

criminal code was passed by the lower house of parliament on April and now goes

to the upper chamber for approval.

In a

separate change, an amendment to the communications law already passed by both

houses of parliament allows the prosecution service to temporarily shut down

websites and even whole networks without obtaining a court order, in order to

prevent the dissemination of information deemed harmful to society or

containing calls to commit “extremist” acts.

Finally,

a government regulation that came into force on April 2 sets out special

reporting rules for the duration of a state of emergency. The owners of print,

radio and TV companies would have to seek prior approval for news content from

emergency management officials, or else face suspension or closure. News pieces

would have to be submitted for scrutiny a day in advance of publication or

broadcast, or one hour in the case of breaking news.

All

three changes have been criticised by media watchdogs.

The OSCE

Representative on Freedom of the Media, Dunja Mijatović, said called on the

Kazak authorities to reconsider measures which she said “might result in undue restrictions of public debate in the media and

access to the internet”.

“The unclearly defined terms and harsh

punishments would allow for a wide interpretation of the law under which the

right of freedom of the media can be limited. This might result in

self-censorship or undue control over media content by the authorities,” Mijatović said.

Kazakstan’s

Union of Journalists said the “false rumours” clause effectively allowed the

authorities to persecute people for expressing an opinion. It warned of the

risk of reverting to “the totalitarian past, the era of fear and terror”.

Djokhar

Utebekov, from the Almaty Association of Lawyers, told the Tengrinews website

that the state-of-emergency rules would allow the authorities to shut down all

internet and mobile communications access within hours.

Lukpan

Ahmedyarov, editor-in-chief of the Uralskaya Gazeta newspaper in western

Kazakstan, added that the rules would “enable

the authorities to make a broad interpretation of what Kazakstan’s domestic

affairs means when the international community accuses [them] of violating

human rights during a state of emergency”.

More

broadly, he said, the various curbs would make it harder to report on public

interest stories.

“Journalists who conduct independent

investigations and who seek out and distribute information will inevitably fall

foul of those who would like to conceal information from public view,” he said.

“They might be corporations, criminal groups or government agencies.”

Two year

ago, Ahmedyarov, whose newspaper is known for its coverage of corruption

issues, was shot and stabbed times by assailants near his home.

Irina

Petrushova, founder of the opposition Respublika media group that includes a

newspaper of the same name which was forced to close in 2012, said she was not

surprised by moves against the media, but suggested that the immediate reason

for rushing in tighter regulation was the unrest in Ukraine earlier this year

which led to President Viktor Yanukovich fleeing the country.

In

Petrushova’s view, the latest attempts to block the free flow of information

betray deep-seated official fears about the state of the economy and other

challenges facing the Kazak government, including the possibility of a

succession battle if President Nursultan Nazarbaev steps down.

Ahmedyarov

said the government realised it was getting harder to influence public opinion

and control what people thought. In his view, the president’s office believes

“that it can’t win the information war, so the only option left to it is just

to block things”.

Galym

Ageleuov, head of the Liberty NGO, believes the government is particularly

intent on increasing its control over the internet – a place where dissent can

still be expressed.

“The authorities tightened the screws on the

print media and then went on to block critical websites. Live Journal, the

Eurasia site and social networks were the last remaining free spaces,” Ageleuov said, adding that the

government clearly feared that “virtual protests” could one day become real

ones.

Ageleuov

noted that bloggers who had established a following were now being targeted. In

February, three of them – Nurali Aitelenov, Rinat Kibraev and Dmitri Scholokov

– spent ten days in jail on public disorder charges after an impromptu protest

against being barred from a press conference given by the mayor of Astana,

Kazakstan’s capital.

All

three are part of a video project called Koz Ashu (“Open Eyes”) which reports

on the persecution of human rights defenders and opposition members, and on

social issues.

Another

blogger, Dina Baidildaeva, was subsequently detained and fined for mounting a

solo protest action against the way the three had been treated. The same month,

another blogger, Andrei Tsyukanov was given 18 days in jail.

Ageleuov

says these people have been marked out as they are engaged in critical citizen

journalism, and are among the few who openly voice criticism of the

authorities.

Earlier

this month, Valery Surganov, who runs a website called Insiderman, was charged

with libel and perverting the course of justice after he criticised the way a

court handled a crime case last year.

Petrushova

pointed to gradual suppression of traditional forms of independent journalism,

a profession that attracts fewer and fewer new recruits.

She

recalled the case of Natalia Sadykova, of the Assandi Times newspaper, who was

accused of the criminal offence of defamation even though she denied authoring

the article concerned, which alleged corruption among local government

officials.

“She was forced to leave the country [on March

9] after they launched a criminal case in connection with an article she didn’t

write,” Petrushova

added.

Assandi

Times was forced to suspend publication down on April 1, after court officers

arrived at its Almaty offices saying they had orders to shut it down.

SOURCE:

IWPR

http://iwpr.net/report-news/kazak-authorities-chip-away-free-expression