The

country’s parliament is debating a series of measures which critics say will

restrict fundamental rights and undermine the effectiveness of the justice

system.

In

addition to proposed amendments to the main Criminal Code, the new Criminal

Procedure Code will alter the way some cases are investigated, while the

Criminal Procedures Implementation Code will change the treatment of prison

inmates. Certain offences are being shifted from the Administrative Offences

Code to the Criminal Code, implying stiffer penalties.

Despite

numerous objections by rights organisations, all four legal codes passed their

initial reading in the Majilis, the lower house of the parliament, in January

and February, while the Criminal Code passed its second reading on April 9.

When the

Majilis finishes with the new bills, they will go to the Senate, the upper

house, for consideration before they go to President Nursultan Nazarbaev to be

signed into law. The government hopes to finalise the work on all the bills

before the summer recess so they can come into force by January 2015.

Some

controversial amendments – such as the retention of the death penalty for acts

of terrorism that result in loss of life – have caused particular alarm amongst

rights defenders.

Although

prosecutions for libel as a criminal offence rather than a civil matter have

long been criticised as a dangerous restriction of free speech, the proposed

Criminal Code will retain this provision.

Previously

administrative offences like running an unregistered religious organisations,

or taking part in a public gathering that has not been approved in advance by

the authorities, are reclassified as crimes.

Last

year, as the government submitted the bills to parliament, the United

States-based watchdog Human Rights Watch warned the Kazak authorities that the

proposed legislation did not comply with international standards.

The

government has played down such criticism, preferring to focus on positive

aspects of the new laws.

Presenting

the changes to parliament at the end of last year, Deputy Prosecutor General

Johann Merkel highlighted elements that he said would reduce the burden on the

prison system.

These

included wider use of alternative punishments such as fines, reclassifying a

number of serious crimes as lesser offences, and making it easier for

vulnerable people including pregnant women and minors to qualify for early

release.

At an

OSCE-supported two-day roundtable discussion on the legal reforms last month,

Alik Shpekbaev, the head of the law enforcement department in the presidential

administration, said the changes would enable Kazakstan “to modernise its

approach to law enforcement approaches and bring legislation into line with

international standards and practices”.

At the

same meeting, Natalia Zarudna, the head of the OSCE centre in Astana, urged the

government to take a “human-rights-oriented approach” in shaping criminal

justice reforms, and to engage legal professionals and civil society in an open

debate about the planned changes.

Yevgeny

Zhovtis, a leading rights activist and founder of the Kazakstan Bureau for

Human Rights and Rule of Law, told IWPR that the authorities were citing the

threat of “extremism” to toughen provisions on civil society groups and

religious activities.

Zhovtis,

who was involved in drafting the existing criminal code back in 1998, said,

“There are even provisions envisaging criminal responsibility for ‘provoking’

labour conflicts, which threaten to put an end to the work of independent trade

unions and workers’ organisations. There are provisions envisaging the use of

the death penalty even though there is an unlimited moratorium on capital

punishment decreed by the president of Kazakstan.”

Zhovtis

said that, driven by fear of the “Arab Spring” uprisings and more recently

events in Ukraine, the Kazak government was “going

down the path of restricting freedom of assembly that is typical of

dictatorships and authoritarian regimes”.

Amangeldy

Shormanbaev, an expert with the International Legal Initiative, says that under

the proposed Criminal Code, both participants in an “unauthorised” gathering

and the owners of premises where it was held would be liable to prosecution.

Speaking at a January round table to discuss the bills, Shormanbaev said that

taking part in such a meeting and disobeying police could result in a prison

sentence of up to two months, whereas previously it was up to 15 days as an

administrative event.

Under

the new criminal code, a police report will automatically trigger a criminal

case involving a full-scale investigation, replacing the current practice of

pre-trial inquiries where evidence is collected in order to determine whether

prosecution is desirable.

Officials

argue that this simplifies pre-trial criminal procedures and makes them more

effective. But experts warn that abolishing the inquiry period will harm the

rights of suspects, who would become the subject of a full-scale criminal case

but still unable to hire a lawyer until they were formally charged.

Another

provision means that leaders of NGO and religious organisations who fail to

register their groups could face a jail term of up to six years.

This

measure was singled out for criticism by United Nations Special Rapporteur,

Heiner Bielefeldt, who used a recent trip to the country to call on the Kazak

government to halt mandatory registration requirements for faith groups.

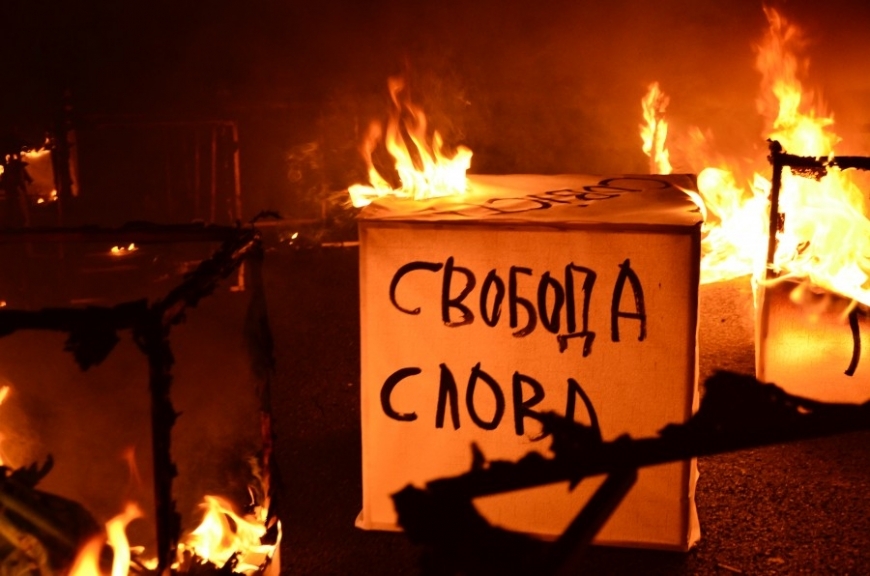

The

continued existence of libel as a criminal offence has alarmed free speech

campaigners. In February, a coalition of media NGOs calling themselves Article

20 published an appeal to Kazakstan’s lawmakers urging them to drop this

provision from the Criminal Code. (See also Internet Censorship Worsens in

Kazakstan.) The media development group Internews-Kazakstan organised a meeting

between industry experts and Majilis deputies as part of a campaign against the

law.

Internews

executive director Marjan Elshibaeva told IWPR that criminal libel law was

often used to muzzle critical voices.

“Any criticism is considered libel. Even an

article written to professional standards where a journalist presents opposing

views could, if need be, interpreted as one-sided, when someone who dislikes it

perceives it to be insulting,” Elshibaeva said.

Galymjan

Khasenov, head of the prison service’s press department, told IWPR that he

supported libel remaining on the books as a criminal offence as a deterrent to

journalists who “present one-sided information without checking” and are “too

lazy” to get an official reaction.

The

draft Criminal Procedures Implementation Code includes changes to the rules

that would cut visits by friends and family members and abolish prison parcels.

The

authorities argue that this is needed to cut the high volume of contraband

getting into prison. Khasenov said the monthly amount of money that convicts

were allowed to spend in prison shops would be increased, and pregnant and

breastfeeding women would still be allowed packages from home.

Regarding

prison visits, Khasenov said they were in line with international standards,

adding that in lower-security institutions the duration of family overnight

visits would remain the same, whereas shorter visits would be extended up to

six hours.

Zhovtis,

who submitted his own assessment of the Penal Code to the parliamentary working

group dealing with the bill, said he welcomed some of its positive aspects. He

pointed to the introduction of a “National Preventive Mechanism” that would see

prisons opened up to inspection by independent public commissions to prevent

torture and the ill-treatment of inmates. This mechanism is set out in the

optional protocol to the international Convention against Torture and Other

Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment,

But

other than that, Zhovtis said, the bill was based on outdated concepts of

“restoring justice and correcting prisoners”, rather than the modern system of

“maintaining the physical and psychological wellbeing of inmates with a focus

on developing skills to help social rehabilitation”.

SOURCE:

IWPR

http://iwpr.net/report-news/changes-kazakstan-criminal-law-seen-threat-human-rights