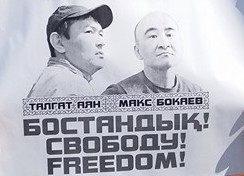

Bokayev, a human rights defender, and Ayanov, an activist, were sentenced to five years imprisonment and banned from engaging in public activities for three years for their alleged roles in organizing peaceful demonstrations. A number of fundamental rights of Bokayev and Ayanov were violated, such as the right to freedom of expression, the right to freedom of assembly, the right to liberty and the right to a fair trial.

Trial observation revealed a number of procedural shortcomings, contradicting Kazakhstan’s obligations under international law. Articles 10 and 11 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) protect the equality of arms, including the right to a public hearing and the presumption of innocence. In the case of Bokayev and Ayanov, several fair trial guarantees were violated, including:

- limited access to a lawyer to prepare hearings and inefficient legal assistance during the trial;

- violation of equality of arms by refusing to examine the defense evidence for no apparent reason and to challenge incriminating evidence;

- violation of the right to a fair and public hearing by limiting access to the courtroom and live coverage of the trial in another room;

- violation of the right to free assistance of an interpreter by ignoring insufficient or lacking knowledge of the accused and the witnesses of the court language and the low quality of translations during the proceedings.

Moreover, the proceedings humiliated the accused that were kept in a glass cage. Such treatment amounts to degrading and inhumane treatment according to article 7 ICCPR.

Legal provisions under which Bokayev and Ayanov were convicted allow an over-broad prohibition of the freedoms of expression and assembly. The charges and convictions against the activists were used as a tool of repression in retaliation for the legitimate activities. The Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (HFHR) and the Netherlands Helsinki Committee (NHC) draw the conclusion that Bokayev and Ayanov should have never been imprisoned.

The NHC and the HFHR call on the governments of the Netherlands and Poland, the European External Action Service, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and other international agencies and bodies in dialogue with the government of Kazakhstan, its branches or officials to:

- include the case and the call for the release of Max Bokayev and Talgat Ayanov in all bilateral talks with the government or relevant public officials of Kazakhstan, in particular, with the judiciary, the prosecutors, officials responsible for economic cooperation, trade and investment;

- condemn criminalization of dissenting opinions and peaceful assembly by the government of Kazakhstan;

- call for the revision of restrictive legislation by Kazakhstan.

The HFHR and the NHC call on the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights Defenders and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Peaceful Assembly and Association to:

- monitor the conditions of detention of Max Bokayev and Talgat Ayanov and call for their release;

- ensure that legal provisions that limit the right to freedom of peaceful assembly in Kazakhstan are aligned with international human rights law; ensure that peaceful assembly is no longer subject to permission by the authorities and prior notification is accepted as sufficient.

The HFHR and the NHC call on the authorities of Kazakhstan to:

- immediately and unconditionally release Max Bokayev and Talgat Ayanov;

- end all forms of harassment, including legal, administrative and tax harassment, of human rights defenders in Kazakhstan and enable them to carry out their work without excessive state interference;

- ensure consistency of government policies with the provisions of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights;

- revise legal provisions that limit the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, ensuring that this right is no longer subject to permission by the authorities and prior notification is accepted as sufficient;

- revise legal provisions that limit the right to freedom of expression, including the vague and broad definition of the offence of incitement to “social, national, clan, class or religious discord” in article 174 of the Criminal Code;

- facilitate very limited application of the restrictive legislation by the courts;

- invite international experts such as the Venice Commission to provide advice on how the legislation applied can be better adapted to international human rights standards.

Monitoring Report Case Bokayev and Ayanov

Background information

In November 2015, the government of Kazakhstan introduced a bill on land privatization. The proposed reform could affect property rights of citizens of Kazakhstan and led to a series of protests across the country in 2015 and 2016. The protests were followed by numerous detentions and prosecutions of protesters and journalists, censoring of news websites and further restrictions on the freedom of assembly.

Human rights defender Max Bokayev and activist Talgat Ayanov were among many protesters in Kazakhstan who stood up against the reform peacefully. They organized a rally on 24 April 2016 and called on their Facebook pages to join the protest. The government deemed their demonstration illegal.

On 17 May 2016, just ahead of a new protest called for 21 May, they were placed in administrative detention. On 20 May 2016, officers of the Division 9 of the National Security Committee in Atyrau, following a court order, searched the house of several human rights defenders including the apartment of Mr. Bokayev’s mother. Officers confiscated documents, computers, telephones, memory sticks and other data storage equipment. During the house search, Mr. Bokayev’s mother was injured and her front door damaged.

On 31 May 2016, one day before the end of their administrative detention, the National Security Committee issued an order charging Mr. Bokayev and Mr. Ayanov with the “preparation of a crime” and “propaganda or public calls for seizure of power or retention of power or violent change of the constitutional order” under articles 24 para. 1 and 179 para. 3 of the Criminal Code. On 21 July 2016, these charges were replaced with “incitement to social, national, ethnic, racial, class or religious hatred” (article 174 para. 2 Criminal Code), “violation of the order of organizing or conducting mass events” (article 400 Criminal Code) and disseminating false information about “emergency situations” or during mass events (article 274 para. 4 pt. 2 Criminal Code).

Criminal proceedings against the activists violate two essential human rights: the rights to the freedom of expression and of peaceful assembly.

Several UN instruments protect the right to freedom of opinion and expression. This includes, for example, the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (“UDHR”) according to which everyone shall “enjoy freedom of speech”. Its article 19 focuses on the right to freedom of opinion and expression.[1] Furthermore, article 19 para. 3 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”)[2] defines under which circumstances the freedom of expression can be restricted: restrictions must be prescribed by law and considered as “necessary” either for “the respect of the rights and reputation of others” or “the protection of national security or of public order or of public health or morals”.[3] Both documents, the UDHR and the ICCPR, also protect the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion in article 18 that, as is the right to freedom of opinion and expression, can be subject to limitations. In this context, article 5 ICCPR calls on governments to avoid infringing upon the rights mentioned above and other rights of the ICCPR. Other UN instruments also address the arbitrary limitation of the right to freedom of expression, especially in the context of politically-motivated trials. According to the ICCPR general comment, the right to freedom of opinion and expression “may never be invoked as a justification for the muzzling of any advocacy of multi-party democracy, democratic tenets and human rights”[4]. Moreover, the Human Rights Committee states that the protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression is of “paramount importance” and “any restrictions to the exercise of this right must meet a strict test of justification”[5].

Article 20 UDHR guarantees the right of peaceful assembly[6] as does article 21 ICCPR, adding that no restrictions can be placed on the exercise of this right unless they are in “conformity with the law” and are “necessary in a democratic society” to protect the national security, public safety, public order, public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others[7]. The right of peaceful assembly is also addressed in various resolutions, such as the Resolution 15/21 of the Human Rights Council that extends the right to “persons espousing minority or dissenting views or beliefs, human rights defenders” and others[8].

Besides, the Human Rights Council highlights that the right of peaceful assembly is “a fundamental human right” that is “essential for public expression of one’s views and opinions and indispensable in a democratic society. This right includes the right to organize and participate in a peaceful assembly and manifestation with the intent to support or disapprove one or another particular cause”[9] . Additionally, any interference with freedom of assembly must be “necessary in a democratic society”, i.e. that “ideas not necessarily favorably received by the government or the majority of the population” are a cornerstone of democratic society[10].

Detention of activists

On 16 May 2016, criminal proceedings were opened against the organizers of the protest, including Mr. Bokayev and Mr. Ayanov.

On 3 June 2016, the investigating judge of Atyrau court no. 2 remanded Mr. Bokayev and Mr. Ayan to two months of pre-trial detention. Due to his poor health (Mr. Bokayev suffers from persistent symptoms of hepatitis C and requires constant medical care), Mr. Bokayev’s lawyer made a request for house arrest, which was rejected. On 27 August 2016, the judge decided to extend the pre-trial detention. The prosecutor argued that “M. Bokayev has a lot of friends in Kazakhstan and abroad and, therefore, a risk of escape is given”. The decisions to grant (continued) detention lacked a legal basis and the judge used a short and standardized formula to justify the detention. During the hearing of 13 October 2016, the defense lawyers’ motion to replace the pre-trial detention with house arrest or a suspended prison sentence was also rejected by the court. This last motion was filed based on the state of health of Mr. Bokayev, whose health deteriorated in detention. The judge dismissed the motion, arguing that Mr. Bokayev had said he felt good during the previous hearing.

The continued detention of activists violates article 9 of the UDHR that states that no person “shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile”.[11] Additionally, article 9 of ICCPR requires that any deprivation of liberty must be in accordance with the law[12]. In this case, the lengthy pre-trial detention can be regarded as a politically-motivated decision. The decision to grant pre-trial detention was unsubstantiated, lacks a sufficient legal basis and the gravity of such a measure is not in accordance with the severity of the alleged crimes committed. The pre-trial detention aims to prevent the two human rights defenders from exercising their right to peaceful assembly. The UN Human Rights Council addressed the legality of such a detention and its arbitrary character in a variety of cases and concluded that pre-trial detention without any “pertinent explanation” constitute a violation of article 9 ICCPR[13].

Proceedings

The case was pending before the court no. 2 of Atyrau and was processed exceptionally fast. Court hearings were scheduled for almost every day. At the first hearing, the presiding judge G. Daulesheva violated procedural law when she refused to recuse herself. According to the international law standards, such a decision has to be reviewed by another judge. The same judge may not decide upon his or her recuse. Moreover, on 10 October 2016, she ordered police protection for herself, arguing that she was dealing with “a political process”, which caused a “public outcry”. Thus, judge Daulesheva admitted the political nature of the proceedings.

The proceedings against both human rights defenders attracted strong public interest. Even though the presiding judge has the duty to ensure the right to a fair and public hearing, the judge dismissed the defense’ motion to accommodate the interested public. Only a few of the numerous observers, journalists and bloggers were able to attend the hearings due to the small size of the courtroom in which the proceedings took place. Some of the observers were asked to follow the trial in another room that provided them with a live coverage of the trial. Additionally, the personal belongings of the observers were searched and their IDs were checked. The observers were not allowed to carry voice recorders or cameras with them.

The court used a glass cage in the dock, which made it difficult for the accused to understand the judge and witnesses. The defense complained several times about the low quality of the translation from Russian into Kazakh, which made the lawyer-client communication even more difficult. The defense also pointed at the inaccurate trial transcript as a result of the poor translation and complained about the limited access to case files, since not every case document was transmitted to the defense (they received only 16 out of 60 CDs that were used during the trial).

Motions to hear defense witnesses and experts were dismissed by the court. The judge repeatedly threatened the defense lawyers that they will be prosecuted for contempt of court. Some witnesses were called and heard through video conferencing. The quality of the video conferencing was poor and witnesses were not heard in court for no apparent reason. Motions pointing at these shortcomings were dismissed. On 2 November 2016, the judge conducted hearings with Russian speaking witnesses in Kazakh and hearings with Kazakh speaking witnesses in Russian. The witnesses did not understand the questions of the judge. One of the witnesses, Kanat Adilkhanov, informed the judge that he does not speak Russian. Despite this, the judge explained his rights in the Russian language. During the same hearing, defense lawyers filed nine motions of which eight were dismissed. Furthermore, the court refused to call Anara Ibraeva, a UN expert on the right to freedom of assembly. The court denied to examine the evidence by the defense. This included press articles showing that the pro-government party Nur-Otan was allowed to organize a protest in the spring of 2016 at the very same place from which the rally organized by Mr. Bokayev and Mr. Ayanov was banned.

On 2 November 2016, the presiding judge spoke in a low voice during the hearing, which made it difficult for the witnesses and defense lawyers to understand the judge. This practice undermined the right to a fair hearing. Public prosecutor Kasym Sadykov violated the court rules and repeatedly interrupted the defense lawyers while they presented evidence. One defense lawyer, Janargul Bokayeva, was unable to examine the testimony given by Gulmira Shakirova as she was interrupted by the public prosecutor. The judge failed to address these wrongdoings. On 3 November 2016, the public prosecutor Kasym Sadykov continued to interrupt the defense. Despite the defense’ complaints, the judge failed to remind the public prosecutor that his actions could lead to disciplinary action. During the hearings that took place on 3 and 4 November 2016, public prosecutors Kasym Sadykov and Marat Khabibulin asked the same questions to the witnesses Erlana Mursalimova and Almata Mukhamedina. The court failed to address this misbehavior. Public prosecutor Kasym Sadykov initimidated one of the witnesses. He shouted at Temirgali Jumashev: “What do you know about the events in April? Respond immediately what you know! You have the duty to answer by law”.

On 3 November 2016, Mr. Ayanov informed the court that he could not access his lawyer. During the hearing, both defendants were kept far away from their defense lawyers which made it difficult for them to advise their clients.

The health of Mr. Bokayev who suffers from persistent symptoms of hepatitis C deteriorated during the trial. A doctor was called to the hearing on 17 October. The accused appeared before the court unshaved because the prison guards refused to give him a razor.

Mr. Ayanov attempted to cut his veins one day before the trial, but was brought to the court on 19 October 2016 despite his poor state of health. Mr. Ayanov did not receive any medical treatment.

The appellate hearings before the Atyrau Oblast Court took place on 16, 18 and 19 January 2017. Since Mr. Bokayev’s lawyer did not come to the hearing, the court appointed another lawyer for him, but he refused his representation. The defense lawyer of Mr. Ayanov lodged a number of motions regarding the evidence taken into account by the first instance court, stating that it was biased. The motions were dismissed. In her final speech, the defense lawyer stressed that the lawfulness of the decision to refuse the organization of the demonstration taken by the lower administrative instance, the local government, was not reviewed by upper instances.

Harassment outside the hearing

Numerous human rights were also violated outside the courtroom. Many local trial observers reported judicial harassment and intimidation. On 23 October 2016, the three human rights defenders Askhat Bersalimov, Kural Medeuov, Suyundyk Aldabergenov were prevented from holding a peaceful protest in support of Mr. Bokayev and Mr. Ayanov. They were arrested and brought before a court. An administrative tribunal remanded them to ten days in pre-trial detention.

On 24 October 2016 at 11:30 pm, Rinat Iskaliyev, an activist who monitored the trial, was beaten up on his way home in Atyrau by a stranger. He was taken to the emergency room, in an ambulance. Civil society representatives in Kazakhstan believe that Mr. Iskaliyev was deliberately injured to keep him from reporting on the trial.

On 2 February 2016, a local observer monitoring the trial for the Netherlands Helsinki Committee and the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights was searched twice at the entrance to the courtroom.

Judgments

On 28 November 2016, the court no. 2 of Atyrau sentenced the activists to five years in prison and banned them from engaging in public activities for three years. Mr. Bokayev and Mr. Ayanov were found guilty of “incitement to social, national, ethnic, racial, class or religious hatred” (article 174 para. 2 Criminal Code), “violation of the order of organizing or conducting mass events” (article 400 Criminal Code) and spreading false information about emergency situations or during mass events (article 274 para. 4 pt. 2 of the Criminal code). The judge read the judgment in less than 15 minutes and in the same courtroom that was used during the trial, which made it impossible to accommodate all people interested in the outcomes of the proceedings in the room.

On 20 January 2017, the judgment was upheld by the Atyrau Oblast Court.

On January 30, families of the activists were informed that Mr. Bokayev and Mr. Ayanov are being transferred to the North of Kazakhstan, over 1500 km away from their home town. The transfer of the activists violates Kazakhstan’s own regulations and is inconsistent with the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules)[14]. According to the Rules, prisoners shall serve their sentences, to the extent possible, in prisons close to their homes or their places of social rehabilitation (Rule 59), in order to facilitate communication with the outside world. Any decision to move a prisoner to a remote detention facility should be duly justified by the authorities. Prisoners should be consulted on the place of their allocation.

[1] UN General Assembly, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 217 A (III) (adopted on 10 December 1948), art 19, http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/ (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[2] UN General Assembly, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171 (adopted on 16 December 1966), http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[3] ICCPR, art 19 para 3.

[4] UN Human Rights Committee, General comment no. 34, Freedoms of opinion and expression, CCPR/C/GC/34 (adopted on 12 September 2011), para. 23. 2011, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/docs/gc34.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[5] Mavlonov and Sa’di v Uzbekistan, UN Doc CCPR/C/95/D/1334/2004, Communication no. 1334/2004 (HRC, 19 March 2009), para. 8.3, http://juris.ohchr.org/Search/Details/1486 (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[6] UDHR, art 20.

[7] ICCPR, art 21.

[8] Human Rights Council Resolution 15/21, A/HRC/RES/15/21 (adopted on 6 October 2010), https://daccess-ods.un.org/TMP/9300345.18241882.html (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[9] Lozenko v Belarus, CCPR/C/112/D/1929/2010, Communication no. 1929/2010 (HRC, 21 November 2014), para 7.4, http://juris.ohchr.org/Search/Details/1885 (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[10] Belyatsky v Belarus, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/90/D/1296/2004, Communication no. 1296/2004 (HRC, 24 July 2007), para 7.3, http://juris.ohchr.org/Search/Details/1355 (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[11] UDHR, art 9.

[12] ICCPR, art 19.

[13] See, e.g., Al-Rabassi v Libya, CCPR/C/111/D/1860/2009, Communication No. 1860/2009 (HRC, 4 September 2014), paras 2.1-2.3, 2.7 and 7.5, http://juris.ohchr.org/Search/Details/1840 (accessed on 23 January 2017).

[14] Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 17 December 2015.