Supplementary Human Dimension Meeting on

promotion of freedom of expression: rights, responsibilities and OSCE

commitments, Vienna, 3-4 July 2014

Joint statement by

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law, Nota Bene,

Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights and International Partnership for Human

Rights

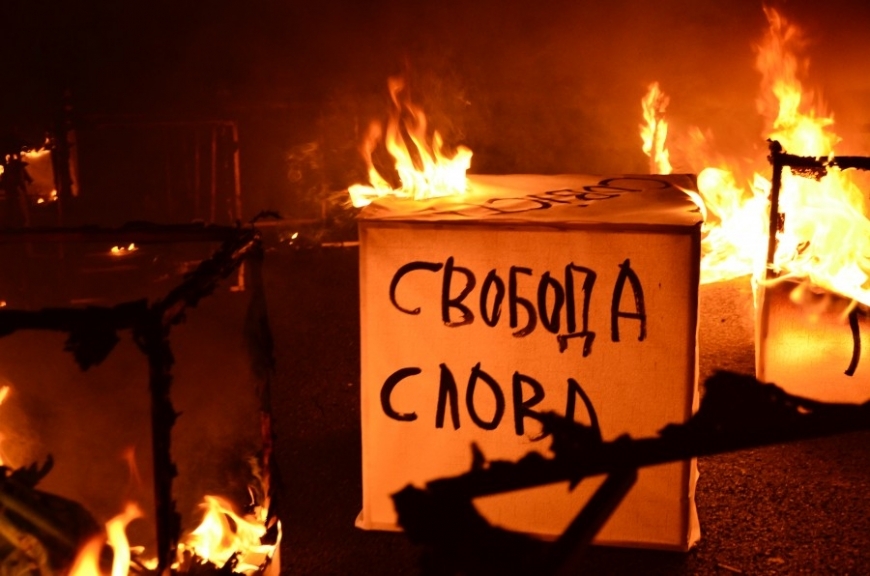

Freedom of expression remains under serious threat in the Central Asian region.

Our organizations would like to use this opportunity to draw attention to

concerns regarding restrictions on media pluralism, internet censorship, and

harassment of journalists and other critical voices in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan

and Turkmenistan, as well as to make recommendations to the governments of

these countries and the OSCE community at large.

Restrictions on media pluralism

Media pluralism in Kazakhstan took a serious blow when a number of

leading opposition media were banned by court for alleged “extremist”

propaganda in late 2012. Following this the crackdown on opposition newspapers

has continued with new apparently politically motivated court decisions. The Pravdivaya Gazeta was closed down in February

2014 for mistakes in the use of publishing information, while the Ashik

Alan was suspended

for three months last autumn for failing to inform authorities about staff

vacation and now is threatened by closure after being ordered to pay close to

8000 EUR for purported copy right violations. In April 2014, a court shut down

the Assandi Times for allegedly being linked to the

previously banned Respublika. In another

case seen as pressure on opposition media, police searched the Astana office of the online channel 16/12 in June 2014 and confiscated technical

equipment, saying it was part of a money laundering investigation. The recently

adopted Administrative Code, which is pending the president’s signature,

retains suspension/closure of media as sanctions for violations of a technical

nature.

The new media law that took effect in Tajikistan in March 2013 introduced strengthened

guarantees for the operating freedom of media outlets and journalists, but lacks effective enforcement mechanisms for

these provisions. The new law provides for complicated registration procedures

for especially print media, which are required to undergo dual registration,

and similarly to in Kazakhstan media outlets may be shut down for

administrative violations. For example, in February this year, the registration

of the weeklyKhafta

was annulled without warning because it had allegedly

published material that was not in line with the direction of its activities

set out in its statutes. The weekly had only issued one edition, which featured

an interview with a national poet who harshly criticized the authorities.

The first ever media law that entered into force in Turkmenistan in January 2013 safeguards freedom of

the media, prohibits censorship and sets out the objective of ensuring media

pluralism. However, in practice the media environment in the country remains fundamentally

repressive. Both print and broadcast media continue to be closely controlled by

the authorities, which interfere with and dictate editorial policies and use

media as means of ideological propaganda to promote a one-sided positive image

of the situation in the country. No new media outlets have been registered

since the new media law entered into force, and as previously there are no

independent media in the country. Access to foreign media is limited,

especially because of restrictions on the import of foreign newspapers and

internet censorship (see below).

Internet censorship

In Kazakhstan, hundreds of internet resources have

been blocked by court because of alleged “extremist” or unlawful content in

proceedings conducted in a quick fashion behind closed doors. Leading

opposition news sites were banned as part of the December 2012 “extremist”

rulings (see above). Cases of blocking of websites without a court decision

also continue to be reported. In 2013-2014, such measures have affected, among

others, news sites such as the Kazakh service of Radio Free Europe/Radio

Liberty and the Uralskaya

Nedelya, and social

and online community sites such as Live Journal, Facebook and Avaaz. The news

portal guljan.org was blocked even after the expiration of a December 2012

court decision, which blocked it for three months for posting information about

unsanctioned peaceful protests, and has now stopped working.

In Tajikistan, websites are also periodically blocked

without a court decision. Such measures are believed to be implemented on the

basis of informal government orders to internet providers and particularly

affect independent local and foreign news sites and social media sites such as

Twitter, Facebook and Vkontakte, which have

been increasingly used as platforms for political discussion. For example, in

December 2013, the government’s communications service reportedly ordered providers to block access to over 100

internet resources, including several social networking sites. Most recently,

in June 2014, Youtube, Gmail and other Google powered services, as well as the

Toj News site became unavailable to the customers of most of the country’s

providers. As on earlier occasions, the government denied having anything to do

with this and blamed the providers. By now access to the sites has been

restored.

Internet penetration in Turkmenistan is the lowest in the Central Asian

region (less than 10% according to available statistics) due to prohibitive costs and the lack

of systematic efforts to promote internet access, in spite of promises made by

the current president. At the same time, internet traffic continues to be

controlled and censored. Foreign-based news sites reporting independently about

the situation in the country, the sites of exiled opposition groups and human

rights organizations (including the site of Turkmen Initiative for Human

Rights, TIHR), social networking sites, and online forums and messaging

applications such as WhatsApp and Wechat are among those that have been

arbitrarily blocked in the country. Proxy servers used to access sites that are

otherwise unavailable are also known to have been blocked.

Harassment of journalists and other

critics

In Kazakhstan, public officials and figures continue

to bring punitive defamation suits involving excessive claims for damages

against journalists and media. Recently there have also been a growing number

of cases where journalists and other outspoken individuals have been criminally

charged with defamation or “incitement of national, religious or social

discord.” In its 2013 monitoring, the Adil Soz free speech foundation documented 82 defamation suits against journalists

and media, where the requests for damages totaled 10 million EUR; 16 criminal

defamation cases; and four “incitement” cases. Among those currently facing

criminal defamation charges are Natalya Sadykova, an independent journalist who

fled the country in March after a case was opened against her over an article

she denies writing, and Valery Surganov, editor of www.insiderman.kz who is on trial for his coverage of a

court case on kidnapping and rape. The recently adopted Criminal Code, which

civil society has urged the president to veto, retains penalties

of up to three years in prison for defamation, as well as enhanced protection

against libel for the president and government officials. Threats and physical

attacks against journalists, which in most cases go unpunished, also remain of

serious concern in the country.

In Tajikistan, libel was de-criminalized in 2012, but

insulting the president and government officials is still subject to criminal

liability, which has a chilling impact on free expression. As in Kazakhstan,

there is a troubling practice of using defamation suits as a means of

retaliation against journalists and media by public officials and figures. In

most cases, courts satisfy such suits. For example, in April 2014, an appeal

court upheld the conviction against the independent Asia

Plus newspaper and

its editor Olga Tutubalina over an article about the country’s intelligentsia.

The National Association of Independent Media in Tajikistan (NANSMIT) documented nine civil and administrative cases and

one criminal case against journalists and media in 2013. Journalists and

bloggers addressing corruption and other sensitive issues also face threats,

arrests and attacks. In a recent case causing an international outcry, PhD student and blogger Alexander Sodiqov, a Tajik

citizen residing in Canada, was arrested in mid-June when conducting research

in the city of Khorog. He was held incommunicado for several days before the

authorities disclosed his whereabouts and said that a criminal case has been

opened against him. He is reportedly suspected of spying.

In Turkmenistan, the few local journalists who

contribute to independent foreign media, as well as members of civil society

who publicly speak up about the situation in the country remain highly

vulnerable to intimidation and harassment. Local correspondents for the

Prague-based Turkmen service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Azatlyk) are regularly

detained, questioned and obstructed by police in other ways when carrying out

their work. Only in December 2013-January 2014, five such incidents were documented. Azatlykcontributor

Rovshen Yazmuhamedov was held for two weeks without explanation in May 2013

after publishing several articles that generated active discussion on the

service’s website. The website of TIHR, a major source of independent

information about developments in Turkmenistan, has repeatedly been the target

of hacker attacks believed to have been orchestrated by Turkmen security

services. Individuals suspected of contributing information to the organization

or otherwise perceived to be associated with it have also been subjected to

pressure. In a recent example, the brother of TIHR’s head Farid

Tuhbatullin was prevented from leaving Turkmenistan in April this year and told

that he and his 9-year-old son are on a list of people banned from travelling

abroad.

Recommendations

Recommendations to the

governments of Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan:

- Ensure that legislation affecting the exercise of

freedom of expression and the media is fully consistent with international

human rights standards, and implement recommendations made by the office

of the OSCE Media Representative and other international and national

experts for revising problematic provisions. - Refrain from adopting and bringing into force new

legislation that does not meet the requirements of international human

rights law with regard to the protection of freedom of expression and the

media. - Put in place concrete mechanisms to enforce

guarantees for the prohibition of censorship and the operating freedom of

media laid down by law, in consultation and cooperation with the OSCE

Media Representative and civil society, and promote the growth of private,

independent media in practice.

Recommendations to the entire community

of OSCE participating States:

- Use bilateral and multilateral contacts, high-level meetings,

public statements and other means to prominently and consistently raise

issues of concern regarding legislation and practices negatively affecting

freedom of expression and the media in individual OSCE countries, as well

as to defend victims of repression. - Support and cooperate with the office of the OSCE

Media Representative in its mandate of helping participating States to

abide by their commitments to freedom of expression and free media. Set a

good example for other OSCE states by implementing relevant

recommendations and best practices identified by this

Representative. - As appropriate, apply the new EU

guidelines on promoting freedom of expression online and offline in third

countries, in particular through the activities of diplomatic

representations. - Regularly consult with civil society on issues

concerning freedom of expression and the media and support civil society

initiatives aimed at promoting improved realization of commitments in this

area in the OSCE region.

http://www.iphronline.org/central-asia-freedom-of-expression-statement-20140703.html