EXECUTIVE SUMMARYS

The Republic of Kazakhstan’s government system and constitution concentrate power in the presidency. The presidential administration controls the government, the legislature, and judiciary as well as regional and local governments. Changes or amendments to the constitution require presidential consent. The 2015 presidential election, in which President Nazarbayev received 98 percent of the vote, was marked by irregularities and lacked genuine political competition. The president’s Nur Otan Party won 82 percent of the vote in the 2016 election for the Mazhilis (lower house of parliament). The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)/Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) observation mission judged the country continued to require considerable progress to meet its OSCE commitments for democratic elections. In June 2017 the country selected 16 of 47 senators and members of the parliament’s upper house in an indirect election tightly controlled by local governors working in concurrence with the presidential administration.

Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces.

Human rights issues included torture; political prisoners; censorship; site blocking; criminalization of libel; restrictions on religion; substantial interference with the rights of peaceful assembly and freedom of association; restrictions on political participation; corruption; and restrictions on independent trade unions.

The government selectively prosecuted officials who committed abuses, especially in high-profile corruption cases; corruption remained widespread, and impunity existed for those in positions of authority as well as for those connected to government or law enforcement officials.

Section 1. Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom from:

- Arbitrary Deprivation of Life and Other Unlawful or Politically Motivated Killings

There were reports the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings or beatings that led to deaths.

On April 30, the body of a 38-year-old resident of Karaganda who was allegedly shot and killed by Temirtau police officer Nurseit Kaldybayev was found in the city outskirts. Investigators proved that Kaldybayev had seized the victim’s car and intended to sell it to make money for his upcoming wedding party. On May 3, Kaldybayev was arrested and charged with premeditated murder. In August the Karaganda specialized criminal court found him guilty of murder and sentenced him to 19 years in jail.

On August 2, the Shakhtinsk Court convicted local prison director Baurbek Shotayev, prison officer Vitaly Zaretsky, and six prisoners–so-called voluntary assistants who receive special privileges in exchange for carrying out orders of prison staff–in the fatal torture of prisoner Valery Chupin. According to investigators, Chupin insulted a teacher at the prison school, and the prison director ordered that the voluntary assistants should discipline him. After brutal beatings and other abuse, Chupin was taken to a local hospital for emergency surgery, but he died. The judge sentenced Shotayev and Zaretsky to seven years of imprisonment each. The six prisoners convicted of carrying out the abuse received extended prison terms ranging from 10 to 17 years.

There were no official reports of military hazing resulting in death; however, there were instances of several deaths that the official investigations subsequently presented as suicides. Family members stated that the soldiers died because of hazing.

On July 15, 21-year-old conscript Bakytbek Myrzambekov died at the Ustyurt frontier station on the Kazakhstani-Turkmen border. According to the official report, on July 9, the soldier complained of food poisoning, was placed in the health unit two days later and died soon after of coronary artery disease. Family members did not believe the official explanation, denied he had heart problems, and asserted that he had died as a result of hazing, citing multiple bruises, including in the pelvic area.

- Disappearance

There were no reports of politically motivated disappearances.

- Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

The law prohibits torture; nevertheless, police and prison officials allegedly tortured and abused detainees. Human rights activists asserted the domestic legal definition of torture was noncompliant with the definition of torture in the UN Convention against Torture.

The National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) against Torture came into force in 2014 when the prime minister signed rules permitting the monitoring of institutions. The NPM is part of the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman and thus is not independent of the government. The Human Rights Ombudsman reported receiving 135 complaints alleging torture, violence, and other cruel and degrading treatment and punishment in 2017. In its April report covering activities in 2017, the NPM reported that despite some progress, problems with human rights abuses in prisons and temporary detention centers remained serious. Concerns included poor health and sanitary conditions; high risk of torture during search, investigation, and transit to other facilities; lack of feedback from prosecutors on investigation of torture complaints; lack of communication with families; discrimination against prisoners in vulnerable groups, including prisoners with disabilities, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) prisoners, prisoners with HIV/AIDS, and other persons from vulnerable groups; and a lack of secure channels for submission of complaints. The report disclosed the problem of so-called voluntary assistants who are used to control other prisoners. Some observers commented that NPM staff lacked sufficient knowledge and training to recognize instances of torture.

In its official report, the prosecutor general indicated 103 cases of torture in the first seven months of the year, of which 16 cases were investigated and forwarded to courts.

Prison and Detention Center Conditions

Prison conditions were generally harsh and sometimes life-threatening, and facilities did not meet international health standards. Health problems among prisoners went untreated in many cases, or prison conditions exacerbated them. Prisons faced serious shortage of medical staff.

Physical Conditions: According to Prison Reform International (PRI), although men and women were held separately and pretrial detainees were held separately from convicted prisoners, during transitions from temporary detention centers, pretrial detention, and prisons, youth often were held with adults.

Abuse occurred in police cells, pretrial detention facilities, and prisons. Observers cited the lack of professional training programs for administrators as the primary cause of mistreatment.

To address infrastructural problems in prisons, authorities closed the eight prisons with the worst conditions. The NPM reported continuing infrastructure problems in prisons, such as unsatisfactory sanitary and hygiene conditions, including poor plumbing and sewerage systems and unsanitary bedding. It also reported shortages of medical staff and insufficient medicine, as well as problems of mobility for prisoners with disabilities. In many places the NPM noted restricted connectivity with the outside world and limited access to information regarding prisoners’ rights. PRI reported that there is widespread concern concerning food and nutrition quality in prisons. Prisoners and former prisoners have complained about their provisions and reported that they were served food past its shelf life.

The government did not publish statistics on the number of deaths, suicides, or attempted suicides in pretrial detention centers or prisons during the year.

Administration: Authorities typically did not conduct proper investigations into allegations of mistreatment. Human rights observers noted that in many cases authorities did not investigate prisoners’ allegations of torture or did not hold prison administrators or staff accountable. The law does not allow unapproved religious services, rites, ceremonies, meetings, or missionary activity in prisons. By law a prisoner in need of “religious rituals” or his relatives may ask to invite a representative of a registered religious organization to carry out religious rites, ceremonies, or meetings, provided they do not obstruct prison activity or violate the rights and legal interests of other individuals. PRI reported that some prisons prohibited Muslim prisoners from fasting during Ramadan.

Independent Monitoring: There were no independent international monitors of prisons. Public Monitoring Commissions (PMCs), quasi-independent bodies that respond to allegations of and attempt to deter torture and mistreatment in prisons, carry out monitoring. In the first 10 months of the year, the PMCs conducted 340 monitoring visits to prisons facilities. Human rights advocates noted that some prisons created administrative barriers to prevent the PMCs from successfully carrying out their mandate, including creating bureaucratic delays, forcing the PMCs to wait for hours to gain access to the facilities, or allowing the PMCs to visit for only a short time.

Authorities began investigating the chair of the Public Monitoring Commission in Pavlodar, Elena Semyonova, on charges of dissemination of false information after she raised the issue of the torture and mistreatment of prisoners to EU parliamentarians in early July. The investigation was ongoing.

According to media reports, Aron Atabek, a poet who has been in prison for 12 years, complained to Semyonova regarding the conditions in his prison. He mentioned his cold, damp cell, his worn clothes, and the information vacuum he was held in without access to letters or television.

Improvements: The 2015 criminal code introduced alternative sentences, including fines and public service, but human rights activists noted they were not implemented effectively.

- Arbitrary Arrest or Detention

The law prohibits arbitrary arrest and detention, but the practice occurred. The government did not provide statistics on the number of individuals unlawfully detained during the year. The prosecutor general reported that during the first six months of the year prosecutors released 423 individuals who were unlawfully held in police cells and offices.

ROLE OF THE POLICE AND SECURITY APPARATUS

The Ministry of Internal Affairs supervises the national police force, which has primary responsibility for internal security, including investigation and prevention of crimes and administrative offenses, and maintenance of public order and security. The Agency of Civil Service Affairs and Anticorruption has administrative and criminal investigative powers. The Committee for National Security (KNB) plays a role in border security, internal and national security, antiterrorism efforts, and the investigation and interdiction of illegal or unregistered groups, such as extremist groups, military groups, political parties, religious groups, and trade unions. In July 2017 the president signed legislative amendments on a reform of the law enforcement agencies, including one giving power to the KNB to investigate corruption by officers of the secret services, anticorruption bureau, and military. The KNB, Syrbar (the foreign intelligence service), and the Agency of Civil Service Affairs and Anticorruption all report directly to the president. Many government ministries maintained blogs where citizens could register complaints.

Although the government took some steps to prosecute officials who committed abuses, impunity existed, especially where corruption was involved or personal relationships with government officials were established.

ARREST PROCEDURES AND TREATMENT OF DETAINEES

A person apprehended as a suspect in a crime is taken to a police office for interrogation. Prior to interrogation, the accused should have the opportunity to meet with an attorney. Upon arrest the investigator may do an immediate body search if there is a reason to believe the detainee has a gun or may try to discard or destroy evidence. Within three hours of arrest, the investigator is required to write a statement declaring the reason for the arrest, the place and time of the arrest, the results of the body search, and the time of writing the statement, which is then signed by the investigator and the detained suspect. The investigator should also submit a written report to the prosecutor’s office within 12 hours of the signature of the statement.

The arrest must be approved by the court. It is a three-step procedure: (1) the investigator collects all evidence to justify the arrest and takes all materials of the case to the prosecutor; (2) the prosecutor studies the evidence and takes it to court within 12 hours; and (3) the court proceeding is held with the participation of the criminal suspect, the suspect’s lawyer, and the prosecutor. If within 48 hours of the arrest the administration of the detention facility has not received a court decision approving the arrest, the administration should immediately release him/her and notify the officer who handles the case and the prosecutor. The duration of preliminary detention may be extended to 72 hours in a variety of cases, including grave or terrorist crimes, crimes committed by criminal groups, drug trafficking, sexual crimes against a minor, and others. The court may choose other forms of restraint: house arrest, restriction of movement, or a written requirement not to leave the city and place of residence. According to human rights activists, these procedures were frequently ignored.

The Prosecutor General reported that the December 2017 amendments to the criminal procedure code reduced the number of causes for arrest and the length of time for preliminary detention from 72 to 48 hours, and cut the number of arrested suspects by 1,500. Authorities held in custody 83 percent of detained individuals for not more than 48 hours.

Although the judiciary has the authority to deny or grant arrest warrants, judges authorized prosecutor warrant requests in the vast majority of cases.

Persons detained, arrested, or accused of committing a crime have the right to the assistance of a defense lawyer from the moment of detention, arrest, or accusation. The 2015 criminal procedure code obliges police to inform detainees concerning their rights, including the right to an attorney. Human rights observers stated that prisoners were constrained in their ability to communicate with their attorneys, that penitentiary staff secretly recorded conversations, and that staff often remained present during the meetings between defendants and attorneys.

Human rights defenders reported that authorities dissuaded detainees from seeing an attorney, gathered evidence through preliminary questioning before a detainee’s attorney arrived, and in some cases used defense attorneys to gather evidence. The law states that the government must provide an attorney for an indigent suspect or defendant when the suspect is a minor, has physical or mental disabilities, or faces serious criminal charges, but public defenders often lacked the necessary experience and training to assist defendants. Defendants are barred from freely choosing their defense counsel if the cases against them involve state secrets. The law allows only lawyers who have special clearance to work on such cases.

Arbitrary Arrest: Prosecutors reported six incidents of arbitrary arrest and detention in the first six months of the year.

The government frequently arrested and detained political opponents and critics, sometimes for minor infractions, such as unsanctioned assembly, that led to fines or up to 10 days’ administrative arrest.

Pretrial Detention: The law allows police to hold a detainee for 48 hours before bringing charges. Human rights observers stated that authorities often used this phase of detention to torture, beat, and abuse inmates to extract confessions.

Once charged, detainees may be held in pretrial detention for up to two months. Depending on the complexity and severity of the alleged offense, authorities may extend the term for up to 18 months while the investigation takes place. The pretrial detention term may not be longer than the potential sentence for the offense. Upon the completion of the investigation, the investigator puts together an official indictment. The materials of the case are shared with the defendant and then sent to the prosecutor, who has five days to check the materials and forward them to the court.

The 2015 criminal code introduced the concept of conditional release on bail, although use of bail procedures is limited. Prolonged pretrial detentions remain commonplace. The bail system is designed for persons who commit a criminal offense for the first time or for a crime of minor or moderate severity not associated with causing death or grievous bodily harm to the victim, provided that the penalties for conviction of committing such a crime contain a fine as an alternative penalty. Bail is not available to suspects of grave crimes, crimes that led to death or were committed by a criminal group, terrorist or extremist crimes, or if there is a justified reason to believe that the suspect would hinder investigation of the case or would escape, or if the suspect violated the terms of bail in the past.

The law grants prisoners prompt access to family members, although authorities occasionally sent prisoners to facilities located far from their homes and relatives, thus preventing access for those unable to travel.

Detainee’s Ability to Challenge Lawfulness of Detention before a Court: The code of criminal procedure spells out a detainee’s right to submit a complaint, challenge the justification for detention, or to seek a pretrial probation as an alternative to arrest. Detainees have 15 days to submit complaints to the administration of the pretrial detention facility or to local court. An investigative judge has three to 10 days to overturn or uphold the challenged decision.

- Denial of Fair Public Trial

The law does not provide for an independent judiciary. The executive branch sharply limited judicial independence. Prosecutors enjoyed a quasi-judicial role and have the authority to suspend court decisions.

Corruption was evident at every stage of the judicial process. Although judges were among the most highly paid government employees, lawyers and human rights monitors stated that judges, prosecutors, and other officials solicited bribes in exchange for favorable rulings in many criminal and civil cases.

Corruption in the judicial system was widespread. Bribes and irregular payments were regularly exchanged in order to obtain favorable court decisions. In many cases the courts were controlled by the interests of the ruling elite, according to Freedom House’s Nations in Transit report for 2018. According to the same report, the process is not public and open as “all participants in criminal processes sign a pledge of secrecy of investigation.” Recruitment of judges was plagued by corruption, and becoming a judge often required bribing various officials, according to the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index report for the year.

Business entities were reluctant to approach courts because foreign businesses have a historically poor record when challenging government regulations and contractual disputes within the local judicial system. Judicial outcomes were perceived as subject to political influence and interference due to a lack of independence. A dedicated investment dispute panel was established in 2016, yet investor concerns regarding the panel’s independence and strong bias in favor of government officials remained. Companies expressed reluctance to seek foreign arbitration because anecdotal evidence suggested the government looks unfavorably on cases involving foreign judicial entities.

Judges were punished for violations of judicial ethics. According to official statistics, during the first nine months of the year authorities convicted two judges for corruption crimes. On June 13, the court in Shymkent convicted Makhta-Aral District Court judge Abay Niazbekov for taking a bribe and sentenced him to 4.5 years of imprisonment and a life ban on working in government offices and state-owned enterprises. On January 30, authorities caught Niazbekov accepting a bribe of 500,000 tenge ($1,360) in his office.

Military courts have jurisdiction over civilian criminal defendants in cases allegedly connected to military personnel. Military courts use the same criminal code as civilian courts.

TRIAL PROCEDURES

All defendants enjoy a presumption of innocence and by law are protected from self-incrimination. Trials are public except in instances that could compromise state secrets or when necessary to protect the private life or personal family concerns of a citizen.

Jury trials are held by a panel of 10 jurors and one judge and have jurisdiction over crimes punishable by death or life imprisonment, as well as grave crimes such as trafficking and engagement of minors in criminal activity. Activists criticized juries for a bias towards the prosecution as a result of the pressure that judges applied on jurors, experts, and witnesses.

Observers noted the juror selection process was inconsistent. Judges exerted pressure on jurors and could easily dissolve a panel of jurors for perceived disobedience of their orders. The law has no mechanism for holding judges liable for such actions.

Indigent defendants in criminal cases have the right to counsel and a government-provided attorney. By law a defendant must be represented by an attorney when the defendant is a minor, has mental or physical disabilities, does not speak the language of the court, or faces 10 or more years of imprisonment. Defense attorneys, however, reportedly participated in only one half of criminal cases, in part because the government failed to pay them properly or on time. The law also provides defendants the rights to be present at their trials, to be heard in court, to confront witnesses against them, and to call witnesses for the defense. They have the right to appeal a decision to a higher court. According to observers, prosecutors dominated trials, and defense attorneys played a minor role.

Domestic and international human rights organizations reported numerous problems in the judicial system, including lack of access to court proceedings, lack of access to government-held evidence, frequent procedural violations, denial of defense counsel motions, and failure of judges to investigate allegations that authorities extracted confessions through torture or duress.

Lack of due process remained a problem, particularly in a handful of politically motivated trials involving opposition activists and in cases in which there were allegations of improper political or financial influence.

Human rights and international observers noted investigative and prosecutorial practices that emphasized a confession of guilt regarding over collection of other evidence in building a criminal case against a defendant. Courts generally ignored allegations by defendants that officials obtained confessions by torture or duress.

POLITICAL PRISONERS AND DETAINEES

The Open Dialog Foundation maintained a list of approximately 24 individuals it considered detained or imprisoned based on politically motivated charges, including land code activist Maks Bokayev and individuals connected to the opposition group Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan, led by fugitive banker Mukhtar Ablyazov, and other individuals connected to Ablyazov. Convicted labor union leader Larisa Kharkova remained under restricted movement, unable to leave her home city without permission of authorities. Human rights organizations have access to prisoners through the framework of the National Preventative Mechanism against Torture.

Land code activist Maks Bokayev was sentenced in 2016 to five years in prison for organizing peaceful land reform protests. Although the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concluded that his imprisonment was arbitrary, he remained in jail.

On October 22, a court in Almaty found businessman Iskander Yerimbetov guilty of fraud for illegally fixing prices in his aviation logistics company and sentenced him to seven years’ imprisonment. Human rights observers criticized numerous violations in the investigation and court proceedings, including allegations of physical mistreatment, and condemned the case as politically motivated. On December 11, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention determined his deprivation of liberty to be arbitrary. The Working Group was concerned by the lack of a warrant at the time of arrest, procedural violations during his detention and trial, and Yerimbetov’s well-being while in detention.

On August 17, authorities released Vadim Kuramshin, a human rights defender designated by civil society organizations as an individual imprisoned on politically motivated charges, on parole after six years in prison.

CIVIL JUDICIAL PROCEDURES AND REMEDIES

Individuals and organizations may seek civil remedies for human rights violations through domestic courts. Economic and administrative court judges handle civil cases under a court structure that largely mirrors the criminal court structure. Although the law and constitution provide for judicial resolution of civil disputes, observers viewed civil courts as corrupt and unreliable.

- Arbitrary or Unlawful Interference with Privacy, Family, Home, or Correspondence

The constitution and law prohibit violations of privacy, but the government at times infringed on these rights.

The law provides prosecutors with extensive authority to limit citizens’ constitutional rights. The KNB, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and other agencies, with the concurrence of the Prosecutor General’s Office, may infringe on the secrecy of private communications and financial records, as well as on the inviolability of the home. Human rights activists reported incidents of alleged surveillance, including KNB officers visiting activists and their families’ homes for “unofficial” conversations regarding suspect activities, wiretapping and recording of telephone conversations, and videos of private meetings posted on social media.

Courts may hear an appeal of a prosecutor’s decision but may not issue an immediate injunction to cease an infringement. The law allows wiretapping in medium, urgent, and grave cases.

Government opponents, human rights defenders, and their family members continued to report the government occasionally monitored their movements.

In July 2017 the prime minister transferred the State Technical Service for centralized management of telecommunication networks and for monitoring of information systems from the Ministry of Information and Communication to the KNB.

Section 2. Respect for Civil Liberties, Including:

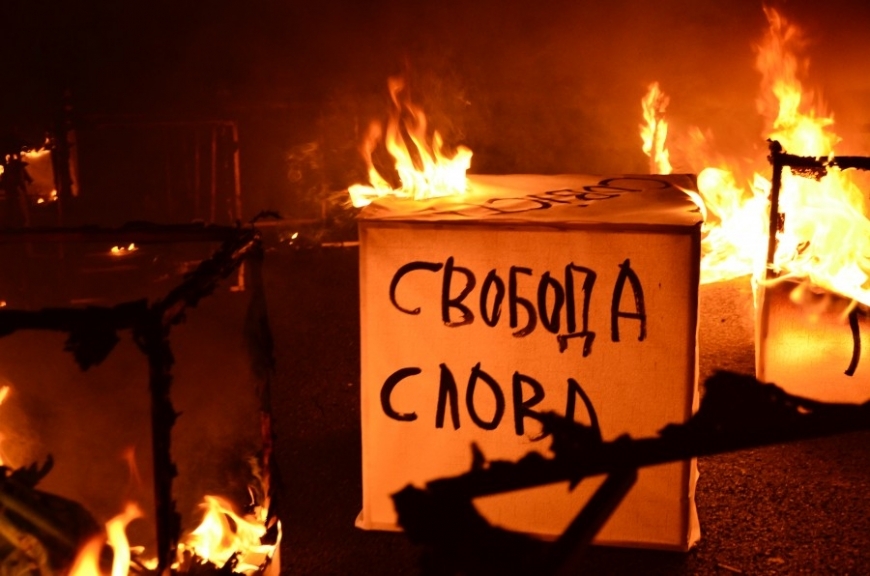

- Freedom of Expression, Including for the Press

While the constitution provides for freedom of speech and of the press, the government limited freedom of expression and exerted influence on media through a variety of means, including laws, harassment, licensing regulations, internet restrictions, and criminal and administrative charges. Journalists and media outlets exercised self-censorship to avoid pressure by the government. The law provides for additional measures and restrictions during “social emergencies,” defined as “an emergency on a certain territory caused by contradictions and conflicts in social relations that may cause or have caused loss of life, personal injury, significant property damage, or violation of conditions of the population.” In these situations, the government may censor media sources by requiring them to provide their print, audio, and video information to authorities 24 hours before issuance or broadcasting for approval. Political parties and public associations may be suspended or closed should they obstruct the efforts of security forces. Regulations also allow the government to restrict or ban copying equipment, broadcasting equipment, and audio and video recording devices and to seize temporarily sound-enhancing equipment.

On May 28, a court suspended the license of independent online newspaper Ratel.kz and banned its chief editor, Marat Asipov, from the publishing world. On March 30, Almaty police opened a criminal investigation against the newspaper, which had reported on the alleged corruption of a former minister. Local and international human rights observers criticized the shutdown of Ratel.kz as an infringement on media freedom.

Freedom of Expression: The government limited individual ability to criticize the country’s leadership, and regional leaders attempted to limit criticism of their actions in local media. The law prohibits insulting the president or the president’s family, and penalizes “intentionally spreading false information” with fines of up to 12.96 million tenge ($40,000) and imprisonment for up to 10 years.

On March 15, police in Shymkent launched a criminal investigation against popular blogger Ardak Ashim, known for her critical posts concerning social issues. Police charged her with incitement of social discord. On March 27, the court held a meeting in the absence of Ashim, her lawyer, or any of her representatives and issued a ruling that she should be placed in a mental hospital for coercive treatment. Local and international human rights defenders demanded immediate release of the blogger, condemned her repression, and named her a prisoner of conscience and victim of punitive psychiatry. On May 5, she was released.

Press and Media Freedom: Many privately owned newspapers and television stations received government subsidies. The lack of transparency in media ownership and the dependence of many outlets on government contracts for media coverage are significant problems. On January 25, the Legal Media Center nongovernmental organization (NGO) lost a lawsuit against the Ministry of Information and Communication challenging the ministry’s refusal to publicize information regarding media outlets that receive government subsidies. The court supported the ministry, determining that such information should be protected as a commercial secret.

Companies allegedly controlled by members of the president’s family or associates owned many of the broadcast media outlets that the government did not control outright. According to media observers, the government wholly or partly owned most of the nationwide television broadcasters. Regional governments owned several frequencies, and the Ministry of Information and Communication distributed those frequencies to independent broadcasters via a tender system.

All media are required to register with the Ministry of Information and Communication, although websites are exempt from this requirement. The law limits the simultaneous broadcast of foreign-produced programming to 20 percent of a locally based station’s weekly broadcast time. This provision burdened smaller, less-developed regional television stations that lacked resources to create programs, although the government did not sanction any media outlet under this provision. Foreign media broadcasting does not have to meet this requirement.

Under amendments to the media law, which entered into force in January, all foreign television and radio channels had to register as legal entities or register a branch office in the country by July 9. The Ministry of Information and Communication cancelled 88 registration certificates because they did not meet registration requirements.

Violence and Harassment: Independent journalists and those working in opposition media or covering stories related to corruption reported harassment and intimidation by government officials and private actors. On June 19, the chief editor and several journalists of independent newspaper Uralskaya Nedelya were summoned by police for interrogation concerning a comment on the newspaper’s YouTube page. An unidentified commenter called on readers to join a protest rally planned for June 23 by the banned Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan movement. The office of the newspaper and the chief editor’s house were searched. At the end of the interrogation, police warned the journalists against participation in the illegal rally.

Censorship or Content Restrictions: The law enables the government to restrict media content through amendments that prohibit undermining state security or advocating class, social, race, national, or religious discord. Owners, editors, distributors, and journalists may be held civilly and criminally responsible for content unless it came from an official source. The government used this provision to restrict media freedom.

The law allows the prosecutor general to suspend access to the internet and other means of communication without a court order. The prosecutor general may suspend communication services in cases where communication networks are used “for criminal purposes to harm the interests of an individual, society, or the state, or to disseminate information violating the Election Law…or containing calls for extremist or terrorist activities, riots, or participation in large-scale (public) activities carried out in violation of the established order.”

By law internet resources, including social media, are classified as forms of mass media and governed by the same rules and regulations. Authorities continued to charge bloggers and social media users with inciting social discord through their online posts.

On September 20, Ablovas Jumayev received a three-year prison sentence on conviction of charges of inciting social discord because he posted messages critical of the government to a 10,000-member Telegram messenger group and allegedly distributed antigovernment leaflets. Jumayev denied the leafleting charges, stating that the leaflets were planted in his car. On Telegram, he had criticized the president’s appointment of a regional police chief. The trial of his wife Aigul Akberdi on similar charges was ongoing.

Libel/Slander Laws: The law provides enhanced penalties for libel and slander against senior government officials. Private parties may initiate criminal libel suits without independent action by the government, and an individual filing such a suit may also file a civil suit based on the same allegations. Officials used the law’s libel and defamation provisions to restrict media outlets from publishing unflattering information. Both the criminal and civil codes contain articles establishing broad liability for libel and slander, with no statute of limitation or maximum amount of compensation. The requirement that owners, editors, distributors, publishing houses, and journalists prove the veracity of published information, regardless of its source, encouraged self-censorship at each level.

The law includes penalties for conviction of defamatory remarks made in mass media or “information-communication networks,” including heavy fines and prison terms. Journalists and human rights activists feared these provisions would strengthen the government’s ability to restrict investigative journalism.

National Security: The law criminalizes the release of information regarding the health, finances, or private life of the president, as well as economic information, such as data on mineral reserves or government debts to foreign creditors. To avoid possible legal problems, media outlets often practiced self-censorship regarding the president and his family.

The law prohibits “influencing public and individual consciousness to the detriment of national security through deliberate distortion and spreading of unreliable information.” Legal experts noted the term “unreliable information” is overly broad. The law also requires owners of communication networks and service providers to obey the orders of authorities in case of terrorist attacks or to suppress mass riots.

The law prohibits publication of any statement that promotes or glorifies “extremism” or “incites social discord,” terms that international legal experts noted the government did not clearly define. The government subjected to intimidation media outlets that criticized the president; such intimidation included law enforcement actions and civil suits. Although these actions continued to have a chilling effect on media outlets, some criticism of government policies continued. Incidents of local government pressure on media continued.

INTERNET FREEDOM

The government exercised comprehensive control over online content. Observers reported the government blocked or slowed access to opposition websites. Many observers believed the government added progovernment postings and opinions in internet chat rooms. The government regulated the country’s internet providers, including majority state-owned Kazakhtelecom. Nevertheless, websites carried a wide variety of views, including viewpoints critical of the government. Official statistics reported that 73 percent of the population had internet access in 2018.

In January, amendments to the media law entered into force. The amended law prohibits citizens from leaving anonymous comments on media outlet websites, which must register all online commenters and make the registration information available to law enforcement agencies on request. As a result most online media outlets chose to shut down public comment platforms.

The Ministry of Defense and Aerospace Industry controlled the registration of “.kz” internet domains. Authorities may suspend or revoke registration for locating servers outside the country. Observers criticized the registration process as unduly restrictive and vulnerable to abuse.

The government implemented regulations on internet access that mandated surveillance cameras in all internet cafes, required visitors to present identification to use the internet, demanded internet cafes keep a log of visited websites, and authorized law enforcement officials to access the names and internet histories of users.

In several cases the government denied it was behind the blocking of websites. Bloggers reported anecdotally their sites were periodically blocked, as did the publishers of independent news sites.

On March 13, a court in Astana banned the Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan movement led by fugitive banker Mukhtar Ablyazov. The same day Minister of Information and Communication Dauren Abayev announced that access to Ablyazov’s social media posts would be restricted. Internet users reported that access to Facebook, Instagram and YouTube were occasionally blocked in the evening at a time coinciding with Ablyazov’s livestream broadcasts. The government denied responsibility and stated that technical difficulties were to blame.

In July the Ministry of Defense and Aerospace Industry reported that it notified the Center of Network Information of violation of the law by 288 websites that hosted harmful software. There were 124 websites blocked for failure to rectify registration data.

Government surveillance was also prevalent. According to Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2018 report, where the country is listed as “not free,” “the government centralizes internet infrastructure in a way that facilitates control of content and surveillance.” Authorities, both national and local, monitored internet traffic and online communications. The report stated that “activists using social media were occasionally intercepted or punished, sometimes preemptively, by authorities who had prior knowledge of their planned activities.”

Freedom on the Net reported during the year that the country maintained a system of operative investigative measures that allowed the government to use surveillance methods called Deep Packet Inspection (DPI). While Kazakhtelecom maintained that it used its DPI system for traffic management, there were reports that Check Point Software Technologies installed the system on its backbone infrastructure in 2010. The report added that a regulator adopted an internet monitoring technology, the Automated System of Monitoring the National Information Space.

ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND CULTURAL EVENTS

The government generally did not restrict academic freedom, although general restrictions, such as the prohibition on infringing on the dignity and honor of the president and his family, also applied to academics. Many academics practiced self-censorship. In January a group of scientists cosigned a letter appealing to the president to resolve corruption in the distribution of grants for scientific work. The scientists criticized the National Science Grants Council for unfair distribution of grants. In response the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and society filed a complaint with police, which opened a case against a scholar of the Almaty Astrophysics Institute for allegedly fabricating signatures in the letter to the president. No further action was reported.

- Freedoms of Peaceful Assembly and Association

FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY

The law provides for limited freedom of assembly, but there were significant restrictions on this right. The law defines unsanctioned gatherings, public meetings, demonstrations, marches, picketing, and strikes that upset social and political stability as national security threats.

The law includes penalties for organizing or participating in illegal gatherings and for providing organizational support in the form of property, means of communication, equipment, and transportation, if the enumerated actions cause significant damage to the rights and legal interests of citizens, entities, or legally protected interests of the society or the government.

By law organizations must apply to local authorities at least 10 days in advance for a permit to hold a demonstration or public meeting. Opposition figures and human rights monitors complained that complicated and vague procedures and the 10-day notification period made it difficult for groups to organize public meetings and demonstrations and noted local authorities turned down many applications for demonstrations or only allowed them to take place outside the city center.

Activists in Almaty applied to hold a public gathering on August 4 to demand police reform following the death of Olympic medalist Denis Ten. The mayor’s office refused the request, stating that the only place designated for public events in Almaty had already been reserved for another event. The Astana mayor’s office similarly declined a demonstration request. The Almaty activists subsequently submitted 31 petitions requesting a gathering to be held any day in the next month; the mayor’s office denied them all.

On May 10, several dozen individuals staged a protest initiated by fugitive banker and leader of the banned opposition group Democratic Choice of Kazakhstan (DCK) Mukhtar Ablyazov to demand the release of political prisoners and an end to torture. The protest had not received government approval. Police dispersed the protestors and detained several, among them random passers-by and minors, according to activists. Some of those detained were punished by court fines or short administrative detentions. The government did not release any official data on the number of detained or punished protestors.

On June 23, the DCK called another unapproved rally. Police preemptively arrested a number of individuals thought to be involved in the protests. Human rights advocacy organizations reported that those detained included passersby, senior citizens, pregnant women, and children. In several cities reporters who came to cover the event were briefly detained. All detainees were taken to police stations and held there for several hours without food or water. Human rights observers criticized police for unjustified detention and numerous procedural violations in holding the detainees in custody. There were no official reports on the number of those detained. Human rights advocates stated that more than a hundred individuals were detained in Almaty, 30 in Astana, and at least a dozen in Shymkent. In some cities protestors dispersed without police involvement.

FREEDOM OF ASSOCIATION

The law provides for limited freedom of association, but there were significant restrictions on this right. Any public organization set up by citizens, including religious groups, must be registered with the Ministry of Justice, as well as with the local departments of justice in every region in which the organization conducts activities. The law requires public or religious associations to define their specific activities, and any association that acts outside the scope of its charter may be warned, fined, suspended, or ultimately banned. Participation in unregistered public organizations may result in administrative or criminal penalties, such as fines, imprisonment, the closure of an organization, or suspension of its activities.

NGOs reported some difficulty in registering public associations. According to government information, these difficulties were due to discrepancies in the submitted documents.

Membership organizations other than religious groups, which are covered under separate legislation, must have at least 10 members to register at the local level and must have branches in more than one-half the country’s regions for national registration. The government considered political parties and labor unions to be membership organizations but required political parties to have 40,000 signatures for registration. If authorities challenge the application by alleging irregular signatures, the registration process may continue only if the total number of eligible signatures exceeds the minimum number required. The law prohibits parties established on an ethnic, gender, or religious basis. The law also prohibits members of the armed forces, employees of law enforcement and other national security organizations, and judges from participating in trade unions or political parties.

According to Maina Kiai, the UN special rapporteur who visited Kazakhstan in 2015, the law regulating the establishment of political parties is problematic as it imposes onerous obligations prior to registration, including high initial membership requirements that prevent small parties from forming and extensive documentation that requires time and significant expense to collect. He also expressed concern regarding the broad discretion granted to officials in charge of registering proposed parties, noting that the process lacked transparency and the law allows for perpetual extensions of time for the government to review a party’s application.

Under the 2015 NGO financing law, all “nongovernment organizations, subsidiaries, and representative offices of foreign and international noncommercial organizations” are required to provide information on “their activities, including information regarding the founders, assets, sources of their funds and what they are spent on….” An “authorized body” may initiate a “verification” of the information submitted based on information received in mass media reports, complaints from individuals and entities, or other subjective sources. Untimely or inaccurate information contained in the report, discovered during verification, is an administrative offense and may carry fines up to 53,025 tenge ($159) or suspension for three months if the violation is not rectified or is repeated within one year. In extreme cases criminal penalties are possible, which may lead to a large fine, suspension, or closure of the organization.

The law prohibits illegal interference by members of public associations in the activities of the government, with a fine of up to 636,300 tenge ($1,910) or imprisonment for up to 75 days. If committed by the leader of the organization, the fine may be up to 1.06 million tenge ($3,180) or imprisonment for no more than 90 days. The law does not clearly define “illegal interference.”

By law a public association, along with its leaders and members, may face fines for performing activities outside its charter. The law is not clear regarding the delineation between actions an NGO member may take in his or her private capacity versus as part of an organization.

The law establishes broad reporting requirements concerning the receipt and expenditure of foreign funds or assets; it also requires labeling all publications produced with support from foreign funds. The law also sets out administrative and criminal penalties for noncompliance with these requirements and potential restrictions on the conduct of meetings, protests, and similar activities organized with foreign funds.

- Freedom of Religion

See the Department of State’s International Religious Freedom Report at www.state.gov/religiousfreedomreport/.

- Freedom of Movement

The law provides for freedom of internal movement, foreign travel, emigration, and repatriation. Despite some regulatory restrictions, the government generally respected these rights. The government cooperated with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other humanitarian organizations to provide protection and assistance to internally displaced persons, refugees, returning refugees, asylum seekers, stateless persons, and other persons of concern.

Abuse of Migrants, Refugees, and Stateless Persons: Human rights activists noted numerous violations of labor migrants’ rights, particularly those of unregulated migrants. The UN International Organization for Migration (IOM) noted a growing number of migrants who were banned re-entry to Russia and chose to stay in Kazakhstan. The government does not have a mechanism for integration of migrants, with the exception of ethnic Kazakh repatriates (oralman). Labor migrants from neighboring Central Asian countries are often low-skilled and seek manual labor. They were exposed to dangerous work and often faced abusive practices. The migrants are in vulnerable positions because of their unregulated legal status; the laborers do not know their rights, national labor and migration legislation, local culture, or the language.

Among major violations of these migrants’ rights, activists mentioned the lack of employment contracts, poor working conditions, long working hours, low salaries, nonpayment or delayed payment of salaries, and lack of adequate housing. Migrant workers faced the risk of falling victim to human trafficking and forced labor, and the International Labor Organization indicated migrants had very limited or no access to the justice system, social support, or basic health services. In its 2018 report the International Federation for Human Rights stated violations of labor migrants’ rights additionally included corruption of police forces’ migration officers and in other government offices. The report noted increased discrimination against migrants in society, exacerbated by their lack of information, education, and language difficulties.

In-country Movement: The government required foreigners who remained in the country for more than five days to register with migration police. Foreigners entering the country had to register at certain border posts or airports where they entered. Some foreigners experienced problems traveling in regions outside their registration area. The government’s Concept on Improving Migration Policy report covers internal migration, repatriation of ethnic Kazakh returnees (oralman), and external labor migration. In 2017 the government amended the rules for migrants entering the country so that migrants from Eurasian Economic Union countries may stay up to 90 days. There is a registration exemption for families of legal migrant workers for a 30-day period after the worker starts employment. The government has broad authority to deport those who violate the regulations.

Since 2011 the government has not reported the number of foreigners deported for gross violation of visitor rules. Individuals facing deportation may request asylum if they fear persecution in their home country. The government required persons who were suspects in criminal investigations to sign statements they would not leave their city of residence.

Authorities required foreigners to obtain prior permission to travel to certain border areas adjoining China and cities in close proximity to military installations. The government continued to declare particular areas closed to foreigners due to their proximity to military bases and the space launch center at Baikonur.

Foreign Travel: The government did not require exit visas for temporary travel of citizens, yet there were certain instances in which the government could deny exit from the country, including in the case of travelers subject to pending criminal or civil proceedings or having unfulfilled prison sentences, unpaid taxes, fines, alimony or utility bills, or compulsory military duty. Travelers who present false documentation during the exit process could be denied the right to exit, and authorities controlled travel by active-duty military personnel. The law requires persons who had access to state secrets to obtain permission from their employing government agency for temporary exit from the country.

Exile: The law does not prohibit forced exile if authorized by an appropriate government agency or through a court ruling.

PROTECTION OF REFUGEES

The government cooperated with UNHCR and other organizations to provide protection and assistance to refugees from countries where their lives or freedom would be threatened on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. There are approximately 600 recognized refugees in the country, and the government recognized six persons as refugees during the first nine months of the year. Both the number of refugee applications and the approval rate by the government declined considerably during the year compared with prior years.

Access to Asylum: The law provides for the granting of asylum or refugee status, and the government has established a system for providing protection to refugees. UNHCR legally may appeal to the government and intervene on behalf of individuals facing deportation. The law and several implementing regulations and bylaws regulate the granting of asylum and refugee status.

The Refugee Status Determination outlines procedures and access to government services, including the right to be legally registered and issued official documents. The Department of Migration Police in the Ministry of Internal Affairs conducts status determination procedures. Any individual seeking asylum in the country has access to the asylum procedure. According to UNHCR, the refugee system suffers from two major issues. First, access to the territory of Kazakhstan is limited. A person who crosses the border illegally may be prosecuted in criminal court, and may be viewed as a person with criminal potential. Second, access to asylum procedures falls short of the international standard. Authorities remain reluctant to accept asylum applications at the border from persons who lack valid identity documents, citing security concerns.

A legislative framework does not exist to manage the movement of asylum seekers between the country’s borders and authorities in other areas. There are no reception facilities for asylum seekers. The government does not provide accommodation, allowances, or any social benefits to asylum seekers. The law does not provide for differentiated procedures for persons with specific needs, such as separated children and persons with disabilities. Asylum seekers and refugees with specific needs are not entitled to financial or medical assistance. There are no guidelines for handling sensitive cases, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) cases.

Employment: Refugees faced difficulties in gaining employment and social assistance from the government. By law refugees have the right to work, with the exception of engaging in individual entrepreneurship. Refugees faced difficulties in accessing the labor market due to local employers’ lack of awareness of refugee rights.

Access to Basic Services: All refugees recognized by the government receive a refugee certificate that allows them to stay in the country legally. The majority of refugees have been residing in the country for many years. Their status as “temporarily residing aliens” hinders their access to the full range of rights stipulated in the 1951 convention and the law. Refugee status lasts for one year and is subject to annual renewal. This year, it became possible for refugees to apply for permanent residency provided that they have a valid passport. Some refugees have already received permanent residency this year, and they are to be eligible to become Kazakhstani citizens after five years. The law also lacks provisions on treatment of asylum seekers and refugees with specific needs. Refugees have access to education and health care on the same basis as citizens, but have no access to social benefits or allowances.

UNHCR reported cordial relations with the government in assisting refugees and asylum seekers. The government usually allowed UNHCR access to detained foreigners to provide for proper treatment and fair determination of status.

The government was generally tolerant in its treatment of local refugee populations.

Consistent with the Minsk Convention on Migration within the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the government did not recognize Chechens as refugees. Chechens are eligible for temporary legal resident status for up to 180 days, as are any other CIS citizens. This temporary registration is renewable, but local migration officials may exercise discretion over the renewal process.

The government has an agreement with China not to tolerate the presence of ethnic separatists from one country on the territory of the other. UNHCR reported three Uighurs received refugee status during the first nine months of the year.

STATELESS PERSONS

The constitution and law provide avenues to deal with those considered stateless, and the government generally took seriously its obligation to ease the burden of statelessness within the country. As of September approximately 6,900 persons were officially registered by the government as stateless. The majority of individuals residing in the country with undetermined nationality, with de facto statelessness, or at heightened risk of statelessness are primarily those who have no identity documents, have invalid identity documents from a neighboring CIS country, or are holders of Soviet-era passports. These individuals typically resided in remote areas without obtaining official documentation.

In July 2017 the president signed a law that allows the government to deprive Kazakhstani citizenship to individuals convicted of a range of grave terrorism and extremism-related crimes, including for “harming the interest of the state.” According to UNHCR, no one has yet been deprived of citizenship under this law.

According to UNHCR the law provides a range of rights to persons recognized by the government as stateless. The legal status of officially registered stateless persons is documented and considered as having permanent residency, which is granted for 10 years in the form of a stateless person certificate. According to the law, after five years of residence in the country, stateless persons are eligible to apply for citizenship. Children born in the country to officially recognized stateless persons who have a permanent place of residence are recognized as nationals. A legal procedure exists for ethnic Kazakhs; those with immediate relatives in the country; and citizens of Ukraine, Belarus, Russia, and Kyrgyzstan, with which the country has agreements. The law gives the government six months to consider an application for citizenship. Some applicants complained that, due to the lengthy bureaucratic process, obtaining citizenship often took years. In summary the law does not provide a simplified naturalization procedure for stateless persons. Existing legislation prevents children of parents without identity documents from obtaining birth certificates, which hindered their access to education, free health care, and freedom of movement.

Persons rejected or whose status of stateless persons has been revoked may appeal the decision, but such appeals involved a lengthy process.

Officially recognized stateless persons have access to free medical assistance on the level provided to other foreigners, but it is limited to emergency medical care and to treatment of 21 contagious diseases on a list approved by the Ministry of Health Care and Social Development. Officially recognized stateless persons have a right to employment, with the exception of government positions. They may face challenges when concluding labor contracts, since potential employers may not understand or be aware of this legal right.

UNHCR reported that stateless persons without identity documents may not legally work, which led to the growth of illegal labor migration, corruption, and abuse of authority among employers. Children accompanying stateless parents were also considered stateless.

Section 3. Freedom to Participate in the Political Process

The constitution and law provide citizens the ability to choose their government in free and fair periodic elections held by secret ballot and based on universal and equal suffrage, but the government severely limited exercise of this right.

Although the 2017 constitutional amendments increased legislative and executive branch authority in some spheres, the constitution continues to concentrate power in the presidency itself. The president appoints and dismisses most high-level government officials, including the prime minister, cabinet, prosecutor general, the KNB chief, Supreme Court and lower-level judges, and regional governors. The Mazhilis must confirm the president’s choice of prime minister, and the Senate must confirm the president’s choices of prosecutor general, the KNB chief, Supreme Court judges, and National Bank head. Parliament has never failed to confirm a presidential nomination. Modifying or amending the constitution effectively requires the president’s consent. Constitutional amendments exempt the president from the two-term presidential term limit and protect him from prosecution.

The law on the first president–the “Leader of the Nation” law–established President Nazarbayev as chair of the Kazakhstan People’s Assembly and of the Security Council for life, granted him lifetime membership on the Constitutional Council, allows him “to address the people of Kazakhstan at any time,” and stipulates that all “initiatives on the country’s development” must be coordinated through him.

Elections and Political Participation

Recent Elections: An early presidential election in 2015 gave President Nazarbayev 97.5 percent of the vote. According to the New York Times newspaper, his two opponents, who both supported the Nazarbayev government, were seen as playing a perfunctory role as opposition candidates. The OSCE stated that the election process in most cases was managed effectively, although the OSCE/Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) election observation mission stated voters were not given a choice of political alternatives and noted that both “opposition” candidates had openly praised Nazarbayev’s achievements. Some voters reportedly had been pressured to vote for the incumbent.

In June 2017 16 of the 47 members of the Senate were selected by members of maslikhats–local representative bodies–acting as electors to represent each oblast (administrative region) and the cities of Astana and Almaty. Four incumbent senators were re-elected, and the majority of the newly elected senators were affiliated with the ruling Nur Otan Party.

As a result of early Mazhilis elections in 2016, the ruling Nur Otan Party won 84 seats, Ak Zhol won seven seats, and the Communist People’s Party of Kazakhstan won seven seats. The ODIHR reported widespread ballot stuffing and inflated vote totals. The ODIHR criticized the election for falling short of the country’s democratic commitments. The legal framework imposed substantial restrictions on fundamental civil and political rights. On election day serious procedural errors and irregularities were noted during voting, counting, and tabulation.

In June the government amended the election law, reducing the independence of local representative bodies (maslikhats). Previously, citizens could nominate and vote for candidates running in elections for the maslikhats. Under the amended law, citizens vote for parties and parties choose who sits on the maslikhats.

Political Parties and Political Participation: Political parties must register members’ personal information, including date and place of birth, address, and place of employment. This requirement discouraged many citizens from joining political parties.

There were six political parties registered, including Ak Zhol, Birlik, and the People’s Patriotic Party “Auyl” (merged from the Party of Patriots of Kazakhstan and the Kazakhstan Social Democratic Party). The parties generally did not oppose President Nazarbayev’s policies.

To register, a political party must hold a founding congress with a minimum attendance of 1,000 delegates, including representatives from two-thirds of the oblasts and the cities of Astana, Turkistan, and Almaty. Parties must obtain at least 600 signatures from each oblast and the cities of Astana, Turkistan, and Almaty, registration from the Central Election Commission (CEC), and registration from each oblast-level election commission.

Participation of Women and Minorities: Traditional attitudes sometimes hindered women from holding high office or playing active roles in political life, although there were no legal restrictions on the participation of women or minorities in politics.

Section 4. Corruption and Lack of Transparency in Government

The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials. The government did not implement the law effectively, and officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity.

Corruption: Corruption was widespread in the executive branch, law enforcement agencies, local government administrations, the education system, and the judiciary, according to human rights NGOs. On July 12, the president signed into law a set of amendments to the criminal legislation mitigating punishment for a variety of acts of corruption by officials, including decriminalizing official inaction, hindrance to business activities, and falsification of documents; significantly reducing the amounts of fines for taking bribes; and reinstituting a statute of limitation for corruption crimes.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Agency on Civil Service Affairs and Combatting Corruption, the KNB, and the Disciplinary State Service Commission are responsible for combating corruption. The KNB investigates corruption crimes committed by officers of the special agencies, anticorruption bureau, and military. According to official statistics, 1,024 corruption-related offenses were registered during the first seven months of the year. The most frequent crimes were bribery (52 percent), embezzlement (21 percent), and abuse of power (17 percent). The government charged 663 officials with corruption, and 1,370 cases were submitted to courts.

On July 12, a court in Astana sentenced the former chairman of the Geology and Subsoil Committee of the Ministry of Investment and Development, Bazarbay Nurabayev, to seven-and-a-half years of imprisonment, confiscation of property, and a lifetime ban on government service. According to the court, Nurabayev systematically schemed to take bribes from businessmen in exchange for subsoil contracts in various regions of the country. He was caught accepting a bribe of $20,000 in March 2017.

Financial Disclosure: The law requires government officials, applicants for government positions, and those released from government service to declare their income and assets in the country and abroad to tax authorities annually. The same requirement applies to their spouses, dependents, and adult children. Similar regulations exist for members of parliament and judges. Tax declarations are not available to the public. The law imposes administrative penalties for noncompliance with the requirements.

Section 5. Governmental Attitude Regarding International and Nongovernmental Investigation of Alleged Abuses of Human Rights

A number of domestic and international human rights groups operated with some freedom to investigate and publish their findings on human rights cases, although some restrictions on human rights NGO activities remained. International and local human rights groups reported the government monitored NGO activities on sensitive issues and practiced harassment, including police visits to and surveillance of NGO offices, personnel, and family members. Government officials often were uncooperative or nonresponsive to their views.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs-led Consultative Advisory Body (CAB) for dialogue on democracy, human rights, rule of law, and legislative work continued to operate during the year. The CAB includes government ministries and prominent international and domestic NGOs, as well as international organization observers. The NGO community generally was positive regarding the work of the CAB, saying the platform enabled greater communication with the government regarding issues of concern. The government and NGOs, however, did not agree on recommendations on issues the government considered sensitive, and some human rights concerns were barred from discussion. NGOs reported that government bodies accepted some recommendations, although, according to the NGOs, the accepted recommendations were technical rather than substantive.

The Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law, Kadyr Kassiyet, the Legal Media Center, and PRI were among the most visibly active human rights NGOs. Some NGOs faced occasional difficulties in acquiring office space and technical facilities. Government leaders participated–and regularly included NGOs–in roundtables and other public events on democracy and human rights.

The United Nations or Other International Bodies: The government invited UN special rapporteurs to visit the country and meet with NGOs dealing with human rights. The government generally did not prevent other international NGOs and multilateral institutions dealing with human rights from visiting the country and meeting with local human rights groups and government officials. National security laws prohibit foreigners, international organizations, NGOs, and other nonprofit organizations from engaging in political activities. The government prohibited international organizations from funding unregistered entities.

Government Human Rights Bodies: The Presidential Commission on Human Rights is a consultative and advisory body that includes top officials and members of the public appointed by the president. The commission reviews and investigates complaints, issues recommendations, monitors fulfillment of international human rights conventions, and publishes reports on some human rights issues in close cooperation with several international organizations, such as UNHCR, the OSCE, the IOM, and UNICEF. The commission does not have legal authority to remedy human rights violations or implement its recommendations in the reports.

A recent constitutional change stipulated that the Human Rights Ombudsman be selected by the Senate; however, the existing ombudsman was appointed by the president. He also serves as the chair of the Coordinating Council of the National Preventive Mechanism against Torture.

The ombudsman did not have the authority to investigate complaints concerning decisions of the president, heads of government agencies, parliament, cabinet, Constitutional Council, Prosecutor General’s Office, CEC, or courts, although he may investigate complaints against individuals. The ombudsman’s office has the authority to appeal to the president, cabinet, or parliament to resolve citizens’ complaints; cooperate with international human rights organizations and NGOs; meet with government officials concerning human rights abuses; visit certain facilities, such as military units and prisons; and publicize in media the results of investigations. The ombudsman’s office also published an annual human rights report. During the year the ombudsman’s office occasionally briefed media and issued reports on complaints it had investigated.

Domestic human rights observers indicated that the ombudsman’s office and the Human Rights Commission were unable to stop human rights abuses or punish perpetrators. The commission and ombudsman avoided addressing underlying structural problems that led to human rights abuses, although they advanced human rights by publicizing statistics and individual cases and aided citizens with less controversial social problems and issues involving lower-level elements of the bureaucracy.

Section 6. Discrimination, Societal Abuses, and Trafficking in Persons

Women

Rape and Domestic Violence: The law criminalizes rape. The punishment for conviction of rape, including spousal rape, ranges from three to 15 years’ imprisonment. There were reports of police and judicial reluctance to act on reports of rape, particularly in spousal rape cases.

Legislation identifies various types of domestic violence, such as physical, psychological, sexual, and economic, and outlines the responsibilities of local and national governments and NGOs in providing support to domestic violence victims. The law also outlines mechanisms for the issuance of restraining orders and provides for the 24-hour administrative detention of abusers. The law sets the maximum sentence for spousal assault and battery at 10 years in prison, the same as for any assault. The law also permits prohibiting offenders from living with the victim if the perpetrator has somewhere else to live, allows victims of domestic violence to receive appropriate care regardless of the place of residence, and replaces financial penalties with administrative arrest if paying fines was hurting victims as well as perpetrators.

NGOs estimated that on average 12 women each day were subjected to domestic violence and more than 400 women died annually as a result of violence sustained from their spouses. Due in part to social stigma, research conducted by the Ministry of National Economy indicated that a majority of victims of partner abuse never told anyone of their abuse. Police intervened in family disputes only when they believed the abuse was life-threatening. Police often encouraged the two parties to reconcile.

On January 22, the Karatau District Court in Shymkent sentenced Khairulla Narmetov to 3.5 years in jail for injuring his wife Umida. In November 2017 he had attacked her with a knife and injured her severely. After a difficult six-hour surgery, doctors managed to save her life. During the court trial, Umida forgave her husband “for the sake of the children,” she said.

The government opened domestic violence shelters in each region. According to the NGO Union of Crisis Centers, there were 28 crisis centers, which provided reliable services to victims of domestic violence. Of these crisis centers, approximately a dozen have shelters.

Other Harmful Traditional Practices: Although prohibited by law, the practice of kidnapping women and girls for forced marriage continued in some remote areas. The law prescribes a prison sentence of eight to 10 years for conviction of kidnapping. A person who voluntarily releases an abductee is absolved of criminal responsibility; because of this law, a typical bride kidnapper is not necessarily held criminally responsible. Law enforcement agencies often advised abductees to sort out their situation themselves. According to civil society organizations, making a complaint to police could be a very bureaucratic process and often subjected families and victims to humiliation.

Sexual Harassment: Sexual harassment remained a problem. No law protects women from sexual harassment, and only force or taking advantage of a victim’s physical helplessness carries criminal liability in terms of sexual assault. In no instance was the law used to protect the victim, nor were there reports of any prosecutions.

According to studies conducted by NGOs, half of all working women (53 percent) were subject to sexual advances from male supervisors and 14 percent received advances from colleagues. None of those women reached out to police with complaints due to shame or fear of job loss.

In March a group of NGOs and media activists set up Korgau123, an organization to support victims of harassment, and launched a hotline.

Coercion in Population Control: There were no reports of coerced abortion or involuntary sterilization.

Discrimination: The constitution and law provide for equal rights and freedoms for men and women. The law prohibits discrimination based on gender. Significant salary gaps between men and women remained a serious problem. According to observers, women in rural areas faced greater discrimination than women in urban areas and suffered from a greater incidence of domestic violence, limited education and employment opportunities, limited access to information, and discrimination in their land and other property rights.

Children

In 2016 the president issued a decree to establish the Office of the Commissioner for Child Rights (Children’s Ombudsman) to improve the national system of child rights protection.

Birth Registration: Citizenship is derived both by birth within the country’s territory and from one’s parents. The government registers all births upon receipt of the proper paperwork, which may come from the parents, other interested persons, or the medical facility where the birth occurred. Children born to undocumented mothers were denied birth certificates.