“He opened our eyes.” Toizhan’s face lit up as she recalled how the leader of her trade union, Amin Yeleusinov, first began spreading the word about worker rights.

Yeleusinov started working at Oil Construction Company (OCC) in the western Kazakhstani city of Aktau in early 2011. In the run-up to August that year, he roused his colleagues into putting together a new collective agreement with their employer. Before long, OCC workers enthusiastically voted him in as their union rep.

“When Amin Yeleusinov turned up, everything became better. Until that point, we had another union. We didn’t even know what a collective agreement was. It was a dark forest to us,” Toizhan told EurasiaNet.org, sitting in a fellow OCC employee’s apartment. Like all OCC workers interviewed by EurasiaNet.org for this story, Toizhan asked to be identified only with a pseudonym for fear of potential repercussions for speaking openly about the situation.

Yeleusinov is now in jail facing charges for fraud. His union faces dissolution as part of a broader effort by Kazakhstan’s government that seems destined to culminate in the liquidation of independent workers’ advocacy groups nationwide.

The story that led to that arrest has it beginnings in the bloody events of December 2011 in Zhanaozen, an out-of-the-way oil town a couple of hours drive east of Aktau. Rattled by a months-long protest there that culminated with police shooting dead more than a dozen rioting workers, President Nursultan Nazarbayev demanded an overhaul of the way companies negotiate with their employees.

“What is going on here? We do not have a sufficiently developed warning system to prevent labor disputes,” Nazarbayev said in a July 2012 speech beamed by teleconference to laborers sitting in halls across the country. “There is inadequate legal liability for those that stir social and labor unrest, which is frequently caused by employers allowing for unacceptable work conditions.”

The president’s remarks were music to the ears of labor activists who had endured years of harassment from employers, police and even the security services. But the changes made to what Nazarbayev termed “our ineffective legislation on trade unions” came as a crushing disappointment.

The trade union law adopted in 2014 required independent labor unions — like the one headed by Yeleusinov — to affiliate with larger unions organized along industry or regional lines. At the same time, authorities have made it more difficult for those larger unions to register.

Those and other provisions designed to raise the bar for the effective operation of prospective unions prompted an International Labor Organization (ILO) committee to request amendments to ease limitations on “the right of workers to form and join trade unions of their own choosing.” Similar appeals from international trade union networks, rights activists and Kazakhstani laborers went unheeded. At the moment, unrepresented workers have effectively only one option – falling into line and joining a state-affiliated union.

The price is being paid by the Confederation of Independent Trade Unions (known in Russian as KNPRK), under whose umbrella the OCC workers hoped to shelter. Following a January 4 ruling in favor of a Justice Ministry suit filed in the South Kazakhstan region, where the union is based, KNPRK now faces permanent closure over what its representatives say are trivial bureaucratic issues.

Speaking in his sparsely furnished Aktau apartment, OCC construction laborer Marat said he and most of his fellow workers were of one mind about what needed to be done. The union led by Yeleusinov declared members would mount a hunger strike.

“We had given no thought to a hunger strike until that point. It all began on January 5,” Marat told EurasiaNet.org.

Marat said the union resorted to less drastic measures in the past to resist the trade union law.

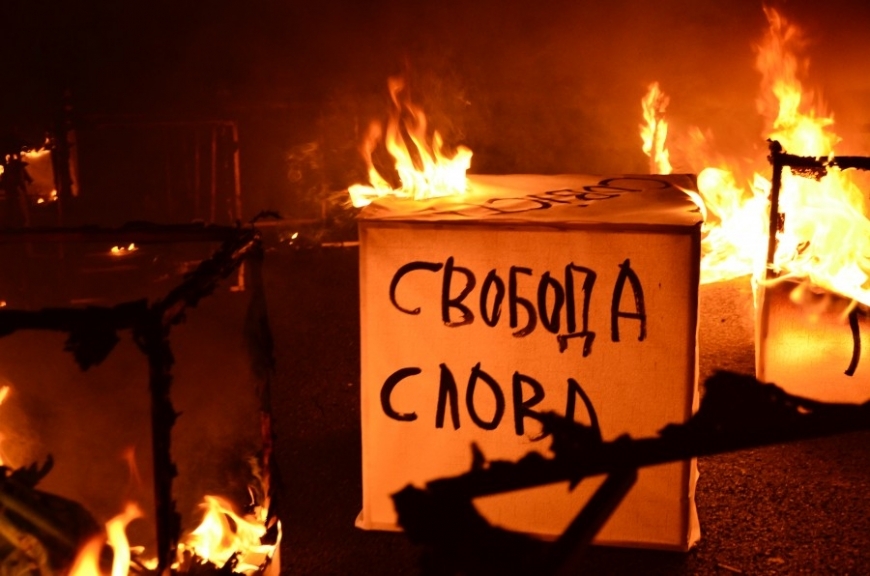

“We expressed our discontent … by marching with signs, we even met with deputies in the Senate in Astana to tell them that [the trade union law] would have a negative effect on the people,” he said. “But it was no use, it brought us no results.”

At any given time, several hundred among the 1,900 or so employees at OCC were taking part in the hunger strike.

Another construction laborer, Aibek, told EurasiaNet.org he took no food for a nine-day period starting from January 6 and still turned out for work. “Of course it was hard, but thanks to God we bore it,” said Aibek.

Every day during the hunger strike, groups of OCC workers would camp out on union premises located a block away from the company headquarters. Those who were there said the mood in the cramped rooms was subdued, but defiant. Strikers sat in wrapped white ribbons bearing the word “hunger” around their heads. At prayer time, the more devout Muslims among them peeled away to perform their rites. Relatives occasionally came to visit, but were turned away for fear of causing distress. Some workers forbade their spouses from coming altogether. From time to time, somebody would bring bottles of water, which the strikers would drink before going to sleep. Medics regularly dropped in on the workers to measure their blood pressures and conduct other routine checks.

If there was one particularly unusual thing about the strike, it was that similar stands have previously been taken over concrete demands, like pay and work conditions, rather than over a matter of principle. But the way OCC employees tell it, the loss of their union could spell trouble ahead.

Western Kazakhstan has had more than its share of industrial disputes. Locals point to the hardship of living in an unyielding and poorly connected part of the world as an underlying cause that explains the workers’ determination.

Aktau is not a beautiful city. And for all the oil riches that abound in the surrounding region, it is not especially prosperous either. Uneven and unpaved sidewalks and poorly paved roads are the norm. Grey Soviet apartment blocks exude an air of decay, and the more recent high-rise buildings are already aging poorly. Online maps show the center of city graced with spacious botanic gardens, but the space is, in reality, largely barren and thinly cultivated. The soil yields few nutrients, so the rare trees planted to liven up the broad patches of sandy scrubland struggle to survive.

There is scant evidence that the bounty generated by Kazakhstan’s oil boom has trickled down to Aktau, which lacks many of the outward vestiges of rising prosperity seen in cities like Astana, or the business capital, Almaty. The most eye-catching Western brand around is the Burger Chain restaurant that towers across the road from the Eternal Flame war memorial.

The city comes into its element as the weather improves, when families hit the extensive seaside promenade. The government is eager for the Caspian coast to become an internal tourist destination, but there is little sign that is working out.

In such conditions, every concession won by Yeleusinov is a matter of celebration by his colleagues. “It began from things like dairy goods, which are now distributed to every worker for their health — before we didn’t have things like that,” OCC worker Marat told EurasiaNet.org.

Marat said Yeleusinov’s other victories included generous wage increases and improvements to workplace safety standards.

Those concessions were wrested from the company in better times. In recent years, Kazakhstan’s economy has been badly hurt by the sharp fall in energy prices.

The OCC standoff began on January 18. On that day, OCC chairman Serik Abdenov came to the workers to deliver them a ruling from a local court finding the protest illegal. Footage filmed by a reporter for RFE/RL’s Kazakhstan service, Radio Azattyq, shows the workers roundly upbraiding Abdenov for rejecting pleas to negotiate. Standing in the corner of the room, also berating Abdenov, was another union leader, Nurbek Kushakbayev.

Caving into the inevitable, the striking laborers filed out of the union HQ on January 20. As they did, many were handed notes summoning them for questioning at a local police station.

The following days brought a flurry of activity in courts at Aktau and the other towns in which the workers live. Some were fined after being found guilty of inciting illegal public protests. OCC also filed suit for damages against dozens of hunger strikers, arguing that their refusal to eat had hurt the company’s bottom line.

On January 20, a posse of police officers arrived at Yeleusinov’s home in Aktau to take him away for questioning at the local precinct. Footage filmed by a neighbor and posted online shows the union leader struggling desperately to avoid being put into a police car. Without his lawyers or colleagues being informed, Yeleusinov was swiftly flown 1,700 kilometers away for further processing in the capital, Astana.

Kushakbayev, the union rep who berated the OCC chairman, was likewise flown secretly to the capital. Only days later did their lawyers find out with certainty what exact charges the men were facing. Yeleusinov is suspected of embezzlement — a crime punishable by up to 12 years in jail — and Kushakbayev is accused of inciting an illegal public protest.

Days after Kushakbayev was first taken into custody, an Astana court held an appeal hearing. Journalists and supporters were refused entry into the courtroom. The court rejected a motion for his release on bail. Yeleusinov has also been denied bail.

OCC did not respond to EurasiaNet.org requests to comment on developments surrounding the strike.

Yeleusinov’s lawyer, Gulnara Zhuaspaeva, says she is exasperated over what she believes is authorities’ over-reaction to the strike. “This was a labor dispute that should have been settled on the spot with the trade unions. It is a labor dispute that should have been settled through a civil process, and not by means of a criminal case,” Zhuaspaeva told EurasiaNet.org.

There is nothing local about this case, however.

Around 1,500 kilometers away, in the city of Shymkent, Larisa Kharkova, the head of KNPRK, the national union whose dissolution first sparked the Aktau strike, has been confronting her own related set of problems.

Kharkova has been involved in union work since the mid-1990s. She studied engineering in Shymkent in the early 1980s, when Kazakhstan was still part of the Soviet Union. In 2011, she retrained as a lawyer. Her union has since its inception — when it was called the Confederation of Free Trade Unions — has advocated on behalf of medics, oil and gas workers, miners, teachers and journalists, among others.

“We are a trade union created by the workers themselves, and for the workers. We were created from the bottom up. Nobody organized us from the top. We do not answer to anybody because the leaders of our unions are the workers themselves,” KNPRK spokeswoman Ludmila Ekzarkhova told EurasiaNet.org.

Kharkova declined to be interviewed by EurasiaNet.org citing fears of intimidation by the authorities.

The KNPRK leader has adopted a combative line over the past two years, as she sought to overcome the bureaucratic complications of legalizing her union. But as the protest in Aktau entered its second week, something suddenly and mysteriously changed.

On January 11, she summoned a press conference in Shymkent to make an announcement. Local media outlets in Kazakhstan tend to rigorously self-censor when it comes to reporting on labor disputes, but turnout at this event was unusually strong. “Right now there is a hunger strike taking place in the Mangystau region. Members of our trade union are going hungry. I believe this must stop. This hunger strike will yield nothing,” Kharkova told reporters.

The remarks were carried widely by state media and outlets toeing the government line.

Furthermore, Kharkova has also said she does not wish to mount a legal appeal to avoid the dissolution of the union. There is a February 12 deadline to file appeal papers.

Ekzarkhova said this drastic change of heart is the result of a systematic campaign of harassment by the authorities. “She was under strong psychological pressure from investigators. They telephoned her every day and summoned her to the investigators’ office for daily interrogations [including Saturday and Sunday],” Ekzarkhova said.

The questioning is ostensibly linked to hazy allegations of financial wrongdoings, although it is not clear that Kharkova has been charged with any crime. Ekzarkhova said any suggestions of impropriety were without foundation.

“The pressure is also being applied to her family. Her son is a dentist at the city’s hospital for children and he was forced to go on leave without pay,” Ekzarkhova said.

A lawyer for Kharkova, Svetlana Katorcha, said the intimidation of her client has gone further than just interrogations and phone calls.

“They stand guard outside her home. They trail her son’s car as he is driving Kharkova around,” Katorcha said, alluding to groups of plainclothes individuals that she said never produced identification. “They go to her son’s place of work. They go to her husband’s place of work.”

Katorcha said her client informed her that the surveillance is carried on around the clock.

Chroniclers of the 2011 Zhanaozen labor dispute well understand the anxieties felt by union representatives.

In August that year, several months before that standoff descended into violence, 29-year old Zhaksylyk Turbaev, an employee at an affiliate of the company where the striking workers were employed, was found dead — the victim of fatal beating. Turbaev had been hoping to be elected head of his union.

Later that same month, the body of an 18-year-old daughter of a striking worker was found in the same town. Investigators later said they caught the killers and insisted it was unrelated to the dispute.

Supporters of the striking OCC workers say the parallels with the run-up to Zhanaozen are hard to miss: arbitrary arrests, draconian fines, reluctance by employers to engage in negotiations, the media blackout on events, and informal intimidation of union representatives.

“I can only imagine what this might all end with,” said Zhuaspaeva, the lawyer for Yeleusinov. “I wish civil society actors, members of parliament and government bodies whose job it is to uphold the law would try to settle this matter at its source by going to these workers in Aktau.”

“We cannot allow another Zhanaozen,” she said.

SOURCE:

EurasiaNet