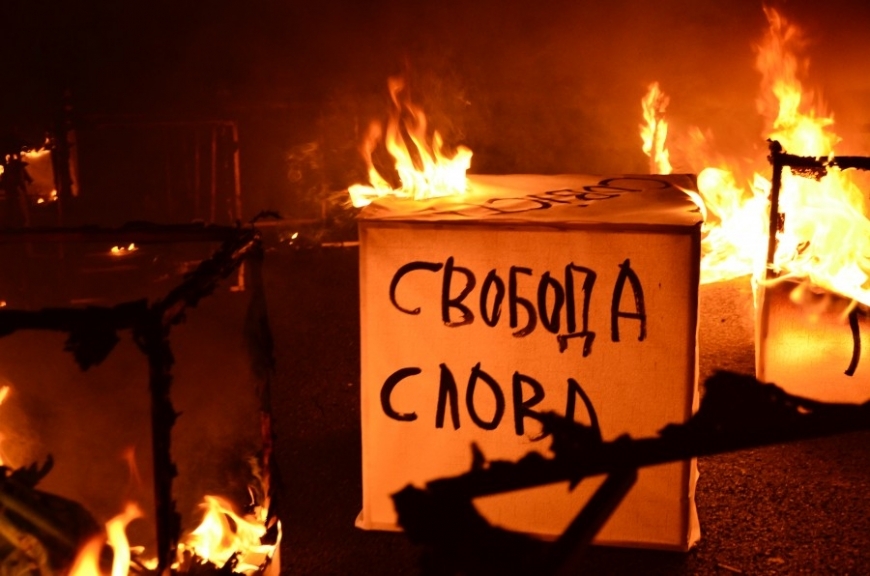

The seven and a half year prison sentence handed to opposition leader Vladimir Kozlov strikes a blow to freedom of expression and pluralism of political voices in

On October 8, 2012, the Aktau City Court in western Kazakhstan found Kozlov, 52, head of the unregistered opposition political party Alga!, guilty of “inciting social discord,” “calling for the forcible overthrow of the constitutional order,” and “creating and leading an organized group with the aim of committing one or more crimes.” The conviction followed an investigation shrouded in secrecy and an unfair trial. The charges relate to Kozlov’s alleged role in violent clashes that took place in western

“Kozlov is paying a heavy price for publicly criticizing the Kazakh government,” said Mihra Rittmann, Europe and

In addition to the lengthy prison sentence, the court ordered Kozlov’s assets seized; these include his apartment and cars, as well as over a dozen Alga! offices registered in his name. The court also ruled that Kozlov and two other defendants must pay trial-related costs amounting to approximately US$10,000.

The two others tried with Kozlov were also found guilty. Akzhanat Aminov, 55, an oil worker from Zhanaozen, was convicted on the same three charges as Kozlov. He will serve a five-year suspended sentence during which he is required to check in with law enforcement and keep them informed of his whereabouts and activities. Aminov was earlier given a one-year suspended sentence for leading an illegal strike in August 2011.

The third defendant, civil society activist Serik Sapargali, 60, was found guilty of “calling for the forcible overthrow of the constitutional order” and will serve a four-year suspended sentence. Aminov had confessed to the charges and Sapargali had admitted partial fault. Both Aminov and Sapargali were released from the courtroom.

One of Kozlov’s lawyers and several civil society activists planning to attend the trial failed to do so because the Air Astana flight from Almaty to Aktau on which they were booked on October 8 was repeatedly delayed and only left Almaty after the trial had already begun. No other flights leaving from Almaty that day experienced such long delays due to weather or other reasons.

From May 2011 until the outbreak of violence on December 16, 2011, oil workers in Zhanaozen had staged peaceful strikes demanding higher wages from their employers. Kozlov and Sapargali were amongst a handful of civil society and political opposition activists who traveled to Zhanaozen to support the oil workers. In June, Kozlov met with striking oil workers.

On January 23, 2012, Kozlov and Sapargali were arrested in Almaty and charged with “inciting social discord” for allegedly persuading fired oil workers to continue their strike and “violently oppose the authorities.” In May, the two men were transferred to a pretrial detention center in Aktau. On February 17, Aminov, 55, was similarly detained on charges of “inciting social discord” in Zhanaozen in relation to his alleged role in leading the strike that ended with the December violence.

Authorities later brought additional charges of “calling for the forcible overthrow of the constitutional order” against all three, and further charged Kozlov and Aminov with “creating and leading an organized group with the aim of committing one or more crimes,” allegedly in collaboration with Muratbek Ketebaev, a member of the Alga! party coordination committee, and Mukhtar Ablyazov, the former chairman of BTA bank in

The criminal investigation, led by the Kazakhstan National Security Committee (KNB), was shrouded in secrecy. At no point in the investigation did the authorities release any evidence of specific speech or actions by the accused that indicated the basis for the charges levied against them.

The trial began on August 16 at the Aktau City Court. The Kazakh authorities said the process would be “open and transparent” and that by allowing independent monitors into the courtroom, they had shown their commitment to “due process and fair trials for all accused.” However, according to independent observers who monitored proceedings, numerous due process violations compromised Kozlov’s right to a fair trial.

Kozlov and his lawyers were given only one day to review the approximately 700-page Russian-language indictment. The court’s translation of proceedings from Kazakh, a language Kozlov does not speak, into Russian, was poor and at times incomplete.

Experts commissioned by the prosecution conducted expert analyses of the defendants’ speech and statements, including secretly recorded telephone and other conversations used as evidence against them in trial. Some of their conclusions were based on review of select phrases, rather than conversations or statements in full. This selectivity had the effect of distorting meanings and compromising the experts’ analysis, and served to cast doubt on the fairness of their assessments.

During the proceedings, the judge also denied important motions made by the defense without explanation. For example, according to trial monitors, Kozlov’s lawyers requested that an investigator be summoned for questioning in connection with possible falsification of testimony after it was discovered that two pages’ worth of two separate witness statements were identical. The judge declined the motion.

The court also admitted into evidence witness testimony collected during the investigation without allowing the defense to cross-examine those witnesses in court, a serious violation of the defendants’ right to a fair trial.

“The court should have ensured a fair trial for these activists, but proceedings fell far short of international standards,” said Rittmann. “The court did nothing to allay fears that this case is arbitrary and politically motivated.”

Human Rights Watch also expressed serious concern about the authorities’ misuse of overbroad criminal charges to target government critics.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly urged the authorities to repeal or amend the charge of “inciting social discord” under article 164 of

Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) provides that “everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression … to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds.” Laws that target speech that incites violence, discrimination, and hostility must respect the core right of free speech and are considered compatible with human rights law only when such violence, discrimination, or hostility is imminent and the measures restricting speech are absolutely necessary to prevent such conduct.

Moreover, the principle of legality under international human rights law requires that crimes be classified and described in precise and unambiguous language so that everyone is aware of what acts and omissions will make them liable and can act in accordance with the law. Article 164, which does not make clear which specific acts are criminal, or what constitutes a “social” group, fails to meet the principles of necessity or legality.

The charge of “calling for the forcible overthrow of the constitutional order” is similarly vague and should be amended so that it meets standards set by international conventions to which

A statement issued on January 25 by the Prosecutor General’s office states that the authorities believe that “one of the causes of the mass disorder [in Zhanaozen] were the active efforts of some individuals to persuade fired workers to continue their protest action and violently oppose the authorities.”

Persuading fired workers to continue their protest action, and indeed supporting them through public statements to the media or in comments to international bodies such as the European Parliament, are legitimate actions under the right to freedom of speech, not crimes, Human Rights Watch said.

“The imprisonment of Kozlov further limits a narrow political landscape in

SOURCE:

Human Rights Watch

www.hrw.org/news/2012/10/09/kazakhstan-opposition-leader-jailed